Is it possible to be innocent and guilty at the same time?

Iconic filmmaker Alfred Hitchcock had a recurring theme in many of his most famous movies – an innocent man is accused of a terrible crime and then spends the remainder of his screen time trying to prove his innocence. All the while, circumstantial evidence layers around him while the police and the actual guilty party close in.

However, in Hitchcock’s world, no one was innocent. Even the wrongly accused had scar tissue – typically, character blemishes that required varying degrees of salvation. Beating the charge was one thing; a cleared name with a reformed persona quite another.

Under such a plot premise, Hitchcock would – cinematically – stuff his leading man into a burlap sack, toss him into a river, observe the inevitable struggle, and then use some spectacular backdrop to highlight his rescue. Most famously, in “North by Northwest”, Hitchcock dangled Cary Grant from Mount Rushmore (or at least a studio mockup) after making him serpentine through 136 minutes of cornfields and crop dusters, staged murders, and international espionage before finally reeling him in – an innocent and changed man.

Thirty-four years before “North by Northwest” made its debut in 1958, there was, sadly, no one around to reel Jimmy O’Connell to safety.

O’Connell, a professional baseball player, didn’t need salvation, though. His naïve identity was as smooth and unmarred as a frozen lake before the first skate. He only needed to have his name cleared, to be found innocent of his crime.

Unlike the movies, though, real-life exoneration isn’t as tidy or timely – if it comes at all – as a script that has been worked and re-worked by a creative team exclusively focused on making it tidy and timely. No, O’Connell’s acquittal quest hadn’t an ounce of Hollywood magic in it.

A big part of O’Connell’s problem was that the only arbiter capable of clearing his name was an utterly ruthless sort, not equipped with either a sympathetic ear or compassionate heart. He dealt entirely in absolutes and brandished the derived determinations viciously, unconcerned with the resulting damage – collateral or not.

Another not-so-minor obstacle stood in O’Connell’s way as well. He was guilty.

Perhaps, “guilty” isn’t the correct term. O’Connell had, indeed, done what they accused him of doing. However, what he had done wasn’t really a crime – certainly, not in a legal sense, and probably not in an ethical sense, either.

Even decades later, the argument isn’t really over whether he committed the act – he had – it is whether or not the act itself merited any sort of punishment.

EXHIBIT A

As context to O’Connell’s case, consider Exhibit A – the “crime” itself.

In 1924, O’Connell was an eager, second-year player for the New York Giants, and, prior to a late-season game against the lowly Philadelphia Phillies, he approached the opposing shortstop, John Sand, with a curious bargain.

O’Connell offered Sand $500 if the Philadelphia player agreed “not to bear down too hard” on the Giants that afternoon. Sand refused and reported the incident to his manager, Art Fletcher.

The Giants won the game, anyway, 5-1.

Although O’Connell and Sand both started for their respective teams, neither did much of any value in the contest. O’Connell had a double in four at-bats but did not figure directly in any of New York’s five runs. And, even with Sand “bearing down” in the ballgame, the Phillies’ shortstop failed to record a hit in four trips to the plate; although he did score Philadelphia’s only run.

The victory clinched the National League pennant for the Giants and punched their second straight ticket to the World Series.

Meanwhile, the Phillies were fated to complete their seventh straight losing season. Simply put, a really good team had beaten a really bad one, and that should have been that.

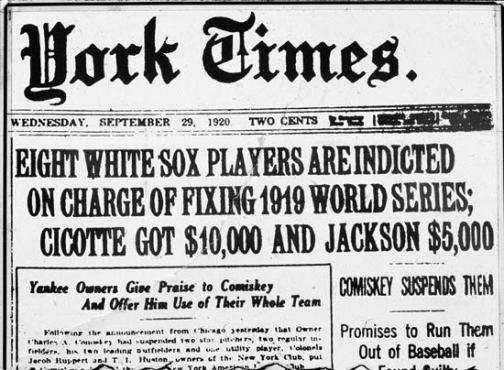

However, word of O’Connell’s bribe attempt swirled from the Phillies’ dugout to the locker room and then all the way the desk of the Commissioner of Baseball, Kenesaw Landis.

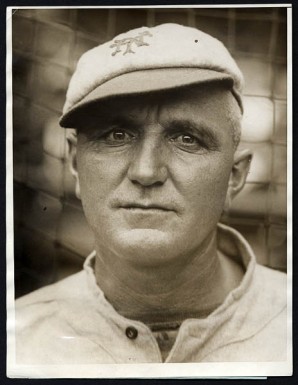

Landis was a humorless, pompous former federal judge from Chicago, who many believed made rulings from the bench as much to satisfy his own sensibilities as on the actual merits of the case. He had been appointed the first Commissioner of Baseball following the scandalous 1919 World Series, in which several members of the American League champion Chicago White Sox took money from gamblers to lose games.

His appointment was designed, in large part, to deal with the public relations mess of the rigged World Series and, by extension, prevent another one from happening.

One of his first official acts as commissioner was to ban the tainted White Sox players from baseball for life. Although only seven Chicago players could be tied, directly or indirectly, to the illicit cash, Landis banned third baseman Buck Weaver as well – even though he hadn’t been paid or actively participated in the conspiracy – for keeping quiet about the plot as it was happening.

To Landis, ignorance slept in the same bed as instigation. That is, what you didn’t do could be as damning as what you did. Moreover, Landis refused to consider any gradients of accountability – there were only those involved and those who were not. And when he affixed punishment, he used an equally rigid scale – the scarlet letters he handed out were all the same size.

So, when it came time to take action on the fixed game that wasn’t fixed in 1924, he ruled on the notion of corruption rather than any resulting fraud. Because of that, the scarlet letter he handed Jimmy O’Connell was precisely the same size as those he handed to the Chicago players who had deliberately disgraced baseball’s most cherished event five years earlier.

O’Connell was banned from organized baseball for life.

Despite the fact that no money was actually exchanged, the Giants-Phillies game itself seemed entirely unaffected, and the transgression was ultimately little more than a young player saying something foolish, Landis saw O’Connell’s brief liaison with duplicity as being just as damaging to the sport as the seven men who took pick axes to the World Series.

Unfortunately, there were no cooler heads around to prevail. When Landis had been appointed commissioner, he had essentially been given tyrannical reign. As part of the deal – made at a time when frightened team owners were desperate for order to be restored in baseball – Landis was made bulletproof. He couldn’t be fired, his decisions couldn’t be reversed unless he nullified them himself, and he required no other counsel before passing judgement.

He was a baseball despot. And for a bombastic, self-important curmudgeon like Landis, that elevated status was intoxicating. He drank up the autonomy like a stranded man in the Kalahari who had just been thrown a great, big canteen of glacier water.

With a more even-handed view, though, most undoubtedly see the staggering difference between O’Connell’s carelessness and the massive gambling conspiracy that swallowed the White Sox. And with a closer look at some of the details and circumstances surrounding O’Connell’s incident, the chasm between his transgression and the dishonesty of the 1919 World Series widens even further, making his punishment seem all the more egregious.

EXHIBITS B & C

Consider, then, Exhibits B and C – motives and mitigating circumstances.

Why on earth would a 24-year old backup outfielder still trying to earn his professional stripes like O’Connell do something as outrageous as offering a bribe to a mediocre player on a floundering team, especially at a time when gambling was so widely condemned and scrutinized in the sport?

Granted, O’Connell’s team – the New York Giants – were in a hotly contested race with Brooklyn for first place in the National League that season. Before the September 27 game with Philadelphia, New York held a narrow 1 ½ game lead over Brooklyn.

O’Connell, eager to prove himself, might have seen convincing an opposing shortstop to gift wrap an important win as a way to get that much coveted badge of approval. As for the consequences – dire as they were at the time – history is peppered with an unending litany of young men in their twenties doing reckless things for validation.

Still, no matter how badly O’Connell wanted to win over his teammates the bribery scheme seems an odd and very impractical way to do it.

First, the Giants really didn’t need any conspiratorial aid in beating the Phillies. On September 27, they were 37 games ahead of Philadelphia in the standings. Paying a player on such a pitiful team to lose to a juggernaut like New York would have been like rewarding a fly for an intentional defeat to the swatter.

The 1924 Giants were also the defending National League champs, so they understood the rigors of a championship run. They were a powerfully built team, with five eventual Hall of Fame players in the starting lineup and one of the game’s greatest managers – John McGraw – leading them from the dugout. They were abundantly capable of beating the best teams in the league, much less dispatching a leaky rowboat like the Phillies.

Also, there was a distinct hierarchy on teams of that time, mostly driven by talent and tenure. Befitting the customary attitude of the day, veteran players regarded their less experienced peers as clear subordinates. And with such a talented roster, the Giants had a clear division of influence in the clubhouse. Older star players had little patience for defiant young teammates.

McGraw, the team’s venerable manager and unquestioned leader, might have summed up the ballclub’s class structure best when he told one of his players, “Don’t ever speak to me. I speak to you and you just shut up.”

That structure worked, though. In his 23rd season with New York, McGraw had already guided the team to three World Series titles and had just captured his tenth National League pennant in 1924.

So, the idea that O’Connell would usurp all of the intimidating layers above him and approach John Sand on his own with the bribe scheme is as unlikely as the need to pay for such an easily attainable win in the first place. No matter how eager he might have been to gain endorsement in the locker room, he surely must have known that independent and impulsive was entirely the wrong way to do it.

Indeed, when Landis called O’Connell in to give his version of events, he told the former judge that New York coach Albert “Cozy’ Dolan had instructed him to make the offer to Sand. Not wanting to disobey a coach’s direct missive but also fearful of the gambling aspect of the errand, O’Connell asked three of the team’s leaders – second baseman Frankie Frisch, first baseman George Kelly, and outfielder Ross Youngs, all future Hall of Famers, by the way – for their guidance.

O’Connell told Landis that the three star players all agreed that he should to do what Dolan had asked.

If true, O’Connell likely felt that he had little choice but to comply. Refusal might bring reprisal and alienation, making big league success and acceptance that much more difficult. Besides, the messenger couldn’t be more culpable than the sender, could he?

However, when Landis questioned the three players, they denied knowing anything. When Dolan was interrogated, he strangely feigned amnesia – neither denying nor admitting guilt, only saying that he could not remember any details of September 27th.

It turns out, the messenger could, indeed, be blamed more than anyone else involved.

Although Dolan was also banned from baseball – Landis didn’t accept memory loss as an acceptable plea – it is hard to equate the exile of a 41-year old coaching assistant who had already played out his big league career with the expulsion of a 24-year old hopeful who would never have the same chance.

In the end, the whole sorry episode was a simply case of testimonial weight – who said what and how much it was believed. No hard evidence was considered, because none existed.

As such, Landis’ decision indicates that he believed O’Connell and Dolan acted in concert and that O’Connell was as responsible for the plot as the older coach. Further, Landis believed that the three star players – Frisch, Kelly, and Youngs – had no involvement and that O’Connell had fabricated their inclusion in the plan.

However, this version of events raises many more questions than it answers.

First, if Landis believed O’Connell when he confessed to his own part in the incident and the involvement of Dolan, why did the judge think that O’Connell then lied about Frisch, Kelly, and Youngs telling him to proceed with the plan? And why would a young player like O’Connell implicate his star teammates if he knew they were innocent? Finally, if Dolan was the instigator, why wouldn’t Landis consider the possibility that O’Connell was coerced into participating, fearful of disobeying his coach’s order?

Though, no matter which version of events is to be believed, the biggest question of all is why was the bribe plan created in the first place?

The likely answer to that is as simple as it is sad.

It was a joke.

Given the nature of ballplayers of the time and the accepted hierarchy of the day, veteran players were notorious for hazing young players as a penance to be paid for membership on the team. As with most hazing, the degrees of the ritual ranged from harmless laughs at a rookie’s expense to physical, psychological torment of a newcomer.

As an example of the latter, the great Ty Cobb was hazed so mercilessly by his older Detroit teammates early in his career that he suffered a nervous breakdown and missed two months of the 1906 season.

Mostly, though, hazing involved variants of the former – the long, arduous crawl of a baseball season practically demanded it. A well-crafted gag that involved a gullible neophyte went quite a way towards livening up an otherwise stale routine.

How else to explain why an impressionable young player like O’Connell would offer money to an opposing player on a bad team at the behest of his coach – and likely three of his veteran teammates?

The very idea of making a greenhorn like O’Connell offer to buy something the older players knew they could get for free would have been worth plenty of laughs. Unfortunately, the premise of the joke involved gambling, and gambling was the great, big boogeyman in the sport.

Once Landis got involved and brought a stenographer into the room, it makes sense – ethics and decency, notwithstanding – why the architects of the joke would have wiped their fingerprints off the whole thing. Whether it was just Dolan or any of the players O’Connell named who were responsible, they probably – and rightfully – figured that admitting participation, even as a joke, to the stone-faced Landis could have dire consequences.

So, Jimmy O’Connell took the fall and as did any hope of his personal baseball glory.

EXHIBIT D

Finally, consider Exhibit D – the punishment and its aftermath.

Ideally, penalties should be partly punitive and part deterrent with an eye towards reform and meted out mostly on the severity of the offense.

In O’Connell’s case, the punitive portion swallowed everything else. He’d essentially been given the same sentence for shoplifting that others had received for armed robbery.

Granted, as a deterrents go, there could be few stronger than a lifetime ban for a minor infraction and first-time offense. However, the impact of the deterrent wasn’t aimed at O’Connell – the punishment had wiped out any chance that he would ever repeat the infraction. Landis wanted to send the message to the rest of the players in the game that gambling of any sort in baseball would not be tolerated. So, he fed O’Connell to the wolves to punctuate the point.

And since part of Landis’ initial mission as commissioner was to ensure that there would not be another tainted World Series, he properly reasoned that fear had to be part of the reform.

However, as a reformer, Landis had his shortcomings in that role as well.

While he exiled a slew of individuals from the game for direct or tangential participation in gambling schemes, most were fringe players at the end of marginal careers. The Black Sox scandal was different only because of the visibility of the mess. In order to put out that fire, Landis knew he would have to stomp on stars like Joe Jackson and Eddie Cicotte.

It is curious, though, how few other notables Landis expelled after that initial purge. Two years after he removed O’Connell, he certainly had the chance to prosecute two of the biggest names in baseball history.

In 1926, Ty Cobb and Tris Speaker were implicated in a betting scheme from 1919 when letters written to one of Cobb’s former teammates, including a letter from Cobb himself, became public. The plan centered mostly around Cleveland, Speaker’s team, deliberately losing a meaningless late-season game to Detroit, Cobb’s team. A group of players, including Speaker and Cobb, were going to pool their money and bet on the Tigers to win, since the outcome had already been agreed upon.

After the letters reached Landis, he made some inquiries and deliberated shortly before dropping the entire matter. Detailed accounts of the arrangement in writing – one directly from the accused – were not enough to sway the great reformer into action.

Either an awful lot had changed in two years or – more likely – Landis had openly shown his preference to sacrifice lambs and spare lions.

There had even been whispers that John McGraw himself was involved in the O’Connell incident back in 1924, paranoid that the Phillies might stumble onto a win or two by accident while Brooklyn passed the Giants by dismantling the pitiful Boston Braves on that final weekend. Even though the practical joke gone awry seems a much more plausible scenario, no one will ever know about the possibility of it actually being McGraw’s brainchild as a genuine bribe, because Landis never interrogated the New York manager.

And if Landis was truly interested in baseball reform, eliminating corruption was only part of it. Integration also had to be a sizeable piece. Of that possibility, he once said, “The colored ballplayers have their own league. Let them stay in their own league.”

His obstinance on the matter – aside from being petty and hateful – played a critical role in keeping African-Americans out of Major League Baseball for decades. Not coincidentally, it took the new baseball commissioner, Albert Chandler, less than two years to see what Landis could not in a quarter of a century, clearing the way for Jackie Robinson’s big league debut in 1947.

As for Jimmy O’Connell, he played in an “outlaw” league in Arizona for a time, because it allowed players banished from organized baseball (Major and sanctioned minor leagues) to participate. Later, he returned to Central California, where he was born and raised, living a long and honorable life until he passed away at the age of 75.

However, it is in that space of time – from 1924 to 1976 – the fifty-two years after he was sacrificed by Kenesaw Landis that remains tinged with melancholy.

No one knows what kind of Major League career O’Connell would have had. The odds of any player becoming a star at the big league level are remarkably slim. Still, O’Connell had shown enough natural ability to attract the attention of John McGraw. And McGraw had a solid record for spotting raw talent and refining it into productive Major League stock.

In fact, O’Connell had impressed McGraw enough to compel the veteran manager to get the Giants to purchase the young player’s minor league contract for $75,000, a record amount for such a procurement at the time.

Playing for the San Francisco Seals of the Pacific Coast League (PCL), O’Connell hit .337 with 17 home runs in 1921 as a 20-year old. The following season, he had a nearly identical stellar year, hitting .335 with 13 homers. And the PCL was a high-quality baseball league, often producing players who went on to star in the majors.

As proof, a decade after O’Connell’s graduation, the PCL showcased the talents of three future Hall of Famers – Joe DiMaggio, Ted Williams, and Ernie Lombardi.

So, when Jimmy O’Connell arrived in New York, there was a basis for hope. He had starred in a league known for producing Major League talent, impressed a legendary manager with a keen eye for playing ability, and was joining a perennial championship-caliber team where he would be surrounded by great players.

Although he struggled for playing time and success during his rookie season, O’Connell saw the field in 87 games, hit six homers, and drove in 39 runs as the Giants cruised to the 1923 National League title.

At the start of the ill-fated 1924 season, though, he languished on the bench, playing in only 21 games through the first four months of the year. Even then, he participated mostly as an afterthought – often entering games as a pinch-hitter or late-game outfield substitute. In fact, in 8 of the 21 games he played during that stretch, he didn’t even get to bat.

However, as injuries depleted the active roster, O’Connell started to play more. In August, he started 11 games and responded to the expansion of his role by hitting .302 for the month. In September, as the Giants raced to stay ahead of Brooklyn, O’Connell responded to the pressure by having his best month in the big leagues. He batted .349 and hit both of the home runs he would tally for the year. In one memorable series against Boston, he collected 9 hits in the four-game set, including a perfect 4-for-4 performance in a 10-2 win.

As if to punctuate his rise as a player on a pennant-winning team, O’Connell had three hits and a home run in the final game of the regular season and, as it turned out, the last game he would ever play in the majors.

New York went on to lose the World Series to the Washington Senators in a tightly contested seven game set. In fact, Game 7 went 12 innings before the Senators finally pushed across the winning run on a bad-hop single.

By then, O’Connell had already been removed from the team and was not allowed to play in the Series. While there is no way of knowing, it is compelling to wonder if having a player who hit nearly .350 in the final weeks of a tight pennant race would have helped swing the results of such a close championship series towards the New Yorkers.

Sadly, like the rest of Jimmy O’Connell’s big league baseball life after September 28, 1924, there are only hypotheticals instead of concrete accomplishments. If there was any real crime committed in 1924, it didn’t involve a rejected bribe; it was the theft of a young man’s future.

They got the wrong man, and Alfred Hitchcock was nowhere to be found to reel him in to safety.

Sources:

http://www.milb.com/milb/history/top100.jsp?idx=44

https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1970&dat=19310324&id=PkwxAAAAIBAJ&sjid=keQFAAAAIBAJ&pg=3461,6239465&hl=en

http://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/primary-resources/rushmore-north-northwest/

http://www.heraldtribune.com/article/20150316/ARCHIVES/503161050

http://www.publicnow.com/view/65A3ABEC2861B7218CAA6DE9E8FE5387A243F14E

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/o/o’conji01.shtml

http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/6032f303

http://articles.latimes.com/2003/feb/16/sports/sp-peterose16/2

https://news.google.com/newspapers?nid=1970&dat=19250109&id=EN4oAAAAIBAJ&sjid=VwYGAAAAIBAJ&pg=1476,871863&hl=en

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/NY1/NY1192409270.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/PHI/

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Kenesaw_Mountain_Landis.aspx

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Ty_Cobb.aspx

http://www.newsday.com/sports/baseball/mets/jenrry-mejia-suspended-for-life-by-mlb-after-third-positive-drug-test-1.11466019

http://articles.chicagotribune.com/1989-05-21/sports/8902030567_1_betting-dutch-leonard-ty-cobb

http://www.milb.com/milb/history/top100.jsp?idx=44

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/gl.cgi?id=o%27conji01&t=b&year=1924

http://www.baseball-reference.com/postseason/1924_WS.shtml

Photos:

http://www.blogcdn.com/blog.moviefone.com/media/2010/06/north-by-northwest-hitchcock-pic.jpg

http://i.ebayimg.com/images/a/(KGrHqN,!iEE68ZGek26BOzcfD2lCg~~/s-l300.jpg

http://images.fineartamerica.com/images-medium-large-5/1-james-j-jimmy-oconnell-retro-images-archive.jpg

http://baseballhall.org/sites/default/files/styles/story_related_hof_254_x_220/public/Landis-Kenesaw-1841.jpg?itok=j4HLd-i9

http://goldenrankings.com/Baseball%20Pictures%202/Ultimate%20Games/1924%20World%20Series/1924NewYorkGiants.jpg

https://goldinauctions.com/ItemImages/000011/11489a_lg.jpeg

https://media1.britannica.com/eb-media/31/126831-004-8F787C6F.jpg

https://uhsaplit.wikispaces.com/file/view/ScarletLetterA.png/92683510/247×323/ScarletLetterA.png

http://www.tradingcarddb.com/Images/Cards/Baseball/72840/72840-5252306Fr.jpg

http://trafficattorneycolorado.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/11/reckless-driving.jpg

https://thumbs.dreamstime.com/t/sunken-rowboat-28666873.jpg

http://www.investors.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/04/MCGRAW-LS-040416-AP.jpg

http://www.thenationalpastimemuseum.com/sites/default/files/field/image/Landis%20LOC.jpg

http://www.thebaseballpage.com/sites/default/files/imagecache/player_page_profile_image/images/baseball_entity/Frankie-frisch.jpg

http://www.gottahaveit.com/ItemImages/000000/4_009978_lg.jpeg

https://i.ytimg.com/vi/OQUO8t7BtnI/maxresdefault.jpg

https://www.detroitathletic.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2015/03/ty-cobb-charles-boss-schmidt-1906-detroit-tigers.jpg

http://www.milb.com/images/2009/10/28/sw5rzxq4.jpg

https://i.ytimg.com/vi/TXaui-m53qM/maxresdefault.jpg