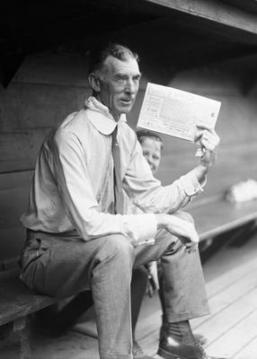

They called him “Victory,” because he brought wins with him – as if pulling them out of his customary derby bowler like some sort of sportsman’s magician.

The real trick, of course, was how he carried all of that winning inside such a modest piece haberdashery. However, the secret behind such sleight of hand resided in only one place – inside the head of the man who wore that magical hat. And a good magician never reveals his secrets.

So, when Charles Victor Faust wandered onto Robison Field in St. Louis seeking the manager of the visiting New York Giants – the legendary and perpetually grumpy John McGraw – he was the only one who knew the furtive key to the team’s inevitable championship success. It was him, only him – Charley Faust, pitcher extraordinaire.

Call it manifest destiny or galactic alignment or whatever term best describes that mysterious mix of fate and symmetrical circumstance, but Faust was certain of its power and his conductive usefulness in bringing McGraw and his underlings baseball glory.

After all, his ironclad belief in such preordained triumph was confirmed by a travelling fortune teller who told him so. And the seer’s vision hadn’t an ounce of vagary – Faust was destined to lead the New York Giants to the 1911 World Series title as one of the greatest pitchers the game had ever seen. Besides, Faust knew that such an agent of the mystic arts couldn’t be mistaken.

There was only one small problem – Faust had no discernible pitching talent. Zero. Nada. Th-th-that’s all, folks.

In fact, Faust’s overall baseball ability was thinner than the lightest dusting of powdered sugar on a stingy helping of french toast. And what McGraw needed for his skilled but floundering ball club during that troubled season was a great, big bag of pure cane sweetener.

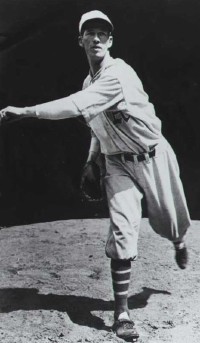

The instant the newcomer went into his cartoonish pitching motion and let fly his first lagging throw McGraw felt his stomach churn. Were it possible for a baseball to ooze through the air, that was precisely how slowly the ball crept forward. Ever the pragmatist, the terse New York leader demonstrated his displeasure – and verdict – by dispensing his glove and catching most of Faust’s audition bare-handed.

McGraw hoped that would be that. A little humiliation went a long way with most people. However, Faust was certainly not like most people.

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

Consider his trek to St. Louis in the first place.

Before that fortune teller conjured up his diamond destiny, Faust led an invisible life. For thirty years, the heat, dust, and hardship of Marion, Kansas had swallowed him up. If anything seemed preordained, it was that Faust – who was born on the family farm in Marion – would die there, too.

And had he a greater level of self-awareness, he likely would have resigned himself to that fate. However, Faust was oblivious to the harsh intersection of social expectancy and personal limitation. Actually, most considered him a simpleton, a dim-witted outcast without a trace of potential.

He was the only one who thought differently. With a childlike naiveté, he latched onto fantastic stories – no matter the unlikeliness of the yarn. So, when he was finally told one with himself as the protagonist, he held onto it with unshakeable resolve – determined to maintain his grip on the tail of that particular frenzied tiger wherever it took him. That it bolted from everything and everyone he knew in Marion solely on the words of a carnival prophet didn’t faze him for an instant.

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

As John McGraw was to find out, a little bare-handed catch proved no match for Faust’s runaway Bengal that afternoon in St. Louis. The lanky, self-appointed savior simply wouldn’t take “no” for an answer. In an effort to embarrass the prodigal imposter into submission, the Giants’ skipper made him take batting practice.

Still dressed in his street clothes and customary bowler, Faust flailed helplessly at the plate until he finally managed to stub the slowest offering. As the ball sputtered a few precious feet away, McGraw urged him to race around the bases.

As with his pitching, Faust’s base running was uncommonly slow. By the time he ambled to second, McGraw implored him to slide. Since he didn’t know how, he mostly just fell – as if he was on fire and was trying to put himself out. The painful tumble repeated itself at third and finally – mercifully – at home.

All the while, the Giants players and most of the pregame crowd howled with laughter. McGraw, himself, couldn’t help a chuckle. Faust – as always – remained oblivious. Now that he had shown New York’s famous manager his pitching and batting prowess, he was ready to assume his rightful place on the team.

To his surprise, McGraw cheerfully but firmly sent him on his way, and the Giants lost the subsequent game to the Cardinals that afternoon.

Undeterred, Faust showed up at the park the next day to continue to plead his case. This time, he was intercepted by New York players who gave him a spare uniform and – as bullies as always do – made him the focus of their ridicule. For sheer sadistic amusement, they urged him to repeat his wild romp around the bases. What they didn’t realize was that Faust felt none of their intended humiliation. He not only basked in the attention, he felt that such an effort put him ever closer to reaching his destiny.

Sensing the team’s lightened mood, McGraw even allowed Faust to stay on the bench – in uniform – to watch the game and provide levity for his players.

The Giants beat the Cardinals handily – ironically, by running the bases flawlessly and relentlessly.

In fact, New York won the next day and the day after that, as well – all with Faust watching anxiously from the bench.

When they left St. Louis, McGraw decided to abandon his eccentric rabbit’s foot. Accordingly, the Giants resumed their pre-Faust struggles, losing four of six games before returning home – solidly in third place.

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

Baseball is filled with superstition. For many players and managers – and even fans – winning and losing isn’t just a matter of skill or lack thereof or of random portions of good and bad luck. Historic losing streaks have been attributed to – among other things – a haunted trade, a cursed billy goat, and a fixed World Series.

Individual success is sometimes traced to wearing the same unwashed garments or eating the same pregame meal or letting facial hair grow to impressive tangles. When that winning karma wears off, the next fortune-inducing ritual is deployed in its place.

For a sport that prides itself on painstaking technique and probability-driven game strategy, it is odd that such irrational tendencies coexist with the otherwise overwhelming logic and precision of baseball – it’s akin to going to the Mayo clinic and getting treated by a witch doctor.

So, when Charley Faust reappeared in New York to greet the stumbling third-place Giants, it should have come as no surprise that the team welcomed back its lanky talisman with open arms.

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

Within a month of having Marion’s luckiest farmer riding shotgun, McGraw’s ball club won 19 of 26 games and surged into first. And it was about this time that Charley morphed into “Victory” Faust – the magical source of the Giants’ winning ways, just as the fortune teller had predicted.

By then, the press had picked up on the story and – realizing what a gold mine of anecdotes and zany adventures they had on their hands – simply let Faust be Faust and raked in the windfall as it tumbled into their laps.

Among the endlessly entertaining things the wide-eyed rural-ite did while unleashed on the unsuspecting city was to secure an inexplicable vaudeville engagement. His “act” was merely to be himself, as he reenacted his base running exploits and his elaborate pitching delivery on stage while audiences hooted with delight.

He was also among the most quotable members of McGraw’s squad. Without hesitation, Faust continued to opine publicly on his confusion as to why he hadn’t been allowed to display his fearsome pitching prowess.

Although he adored all of the attention he received, Faust was troubled by how New York won all of those games – without his direct help. While the impressive string of victories satisfied a part of the vision that guided him to the Giants, it lacked the most important element – as far as he was concerned – him, in the middle of the action.

After all, what good was it to be so close to the field – his toes were practically inside the foul lines – without the chance to lead his team to glory? No, Faust knew he had to convince McGraw to put him in a live game in order to fulfill his destiny.

And when he finally did, the baseball universe would never be the same.

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

The Giants clinched the National League pennant on October 5. However, New York still had a full week’s worth of meaningless games to survive before the start of the World Series.

So, on October 7 – the first of such contests – McGraw considered his options; gave a long, hard look at the very end of his bench; and decided to let all hell break loose.

Trailing 4-2 to the dreadful Boston Rustlers, he summoned Faust – the epicenter of ridicule, the very heart of derision – to pitch the ninth inning of this otherwise empty contest.

And from the very moment he stepped onto the field, Faust lived up to every bit of the spectacle. To acknowledge the stunned but lusty applause of the home crowd, he not only took a bow, he performed a luxuriously sweeping genuflection – melting nearly prostrate to the ground in appreciation.

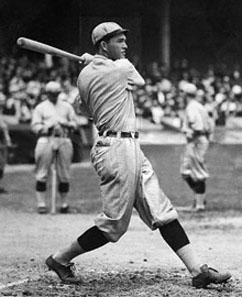

Once on the mound, he went into his dramatic windup – leaning backwards as if pushed by a violent gale, pulling his arms behind his head as far as they would go, and then sweeping his throwing arm forward in big windmill-like fashion. For all of that smoke and fury, the results were just as they were that very first day he stepped on the field in St. Louis – pitches that practically defied all laws of physics by remaining airborne while crawling forward.

Perhaps, Boston’s Bill Rariden – Faust’s first-ever batting opponent – was so mesmerized by the sight of the odd contortions from the mound or that New York’s unofficial mascot was actually in an official Major League game that he couldn’t bring himself to swing at the first two offerings. Nonetheless, both were strikes – slow as hourglass sand but strikes, all the same.

Fearing the utter humiliation of striking out under such circumstances, Rariden came out of his trance just long enough to belt the next pitch deep into left field for a double.

Undaunted, Faust kept going into his manic windup and kept throwing his utterly hittable lobs. Inexplicably, the next three batters made outs. Although Rariden did eventually score on a sacrifice fly, Faust had not only realized his goal of appearing in a live game he performed surprisingly well, pitching a full inning while only allowing a single run.

As if the day couldn’t get any stranger, the game still had another half-inning to go and it did, indeed, get more bizarre.

Needing three runs to tie the score, the Giants were down to their final out when catcher Grover Hartley stepped up to the plate. However, few fans likely noticed Hartley because all eyes were fixed on the player standing on deck, the Kansas phenom himself – Victory Faust.

Although Hartley couldn’t extend the game and made the final out, Faust simply refused to leave. With a juvenile’s insistence to make reality conform to his desires, Faust walked into the batter’s box, anyway.

Sensing an opportunity to enliven an otherwise awful year, Boston players went along for the ride. Allowing the enthusiastic but woefully unskilled hitter to tap a ball into play, the Rustlers bungled throws and tags while Faust furiously circled the bases.

As he rounded third and anticipated scoring, Faust couldn’t help himself and went into a frantic and awkward slide. Unfortunately, he was tagged out – more than ten feet short of home plate.

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

If it had ended there, it would have been a remarkable thing. Faust had appeared in a Major League game and would forever be part of baseball’s official record. He had dreamed of being a big league player and – thanks to one inning of cosmic serendipity – he was.

However, it didn’t end there.

On the last day of the 1911 season, the Giants played an arduous and unenviable doubleheader against Brooklyn. And with the light of the long year fading at last, McGraw called on his eager right-hander one more time.

In the ninth inning of New York’s final regular season game, Faust took the mound with the Giants trailing 5-1 and proceeded to retire the side without giving up a run. Although nothing had changed in terms of his pitching ability – or lack thereof – he accomplished what many pitchers of legitimate skill fail to do, hold a big league lineup scoreless for an inning.

As it turned out, his encore surpassed his debut in every imaginable way.

After dispatching Brooklyn without denting the scoreboard, he lead off New York’s half of the ninth – finally securing a much coveted Major League at-bat, the earlier farce against Boston notwithstanding.

Whether the Brooklyn players felt sorry for the enthusiastic but hapless Faust or if they had ultimately been charmed by his unabashed earnestness, they made sure his trip to the plate was a success. Of course, given a hitter of Faust’s “unique” talents, such an undertaking wasn’t as it easy as it sounded.

If he made contact, he would undoubtedly race around the bases without stopping – or thinking – and Brooklyn would be forced to kick the ball around in an actual Major League game until he eventually barrel-rolled into home. The only plausible way to prevent that was to get him to first base without the complications of having the ball put in play.

So, Brooklyn pitcher Eddie Dent hit him.

Once he was on base, Faust had a bit of a quandary. He had been so used to racing around the bases directly from the batter’s box that he wasn’t quite sure what to do from first. So, he improvised, and stole second base.

Sensing how easy stealing bases was – never mind that the catcher hadn’t bothered to throw until after the fact – Faust pilfered third as well. And when New York third baseman Buck Herzog grounded out, the Giants’ most celebrated rookie came lumbering home.

Although the final box score read – Brooklyn 5, New York 2; it just as easily could have read – Victory Faust 1, Probability 0.

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

Faust’s long, dizzying fall from grace was probably inevitable, but there was an undeniable heartbreak to it.

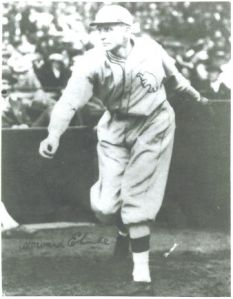

His fortunes as the Giants’ good luck charm – the only real value he had in John McGraw’s eyes – turned sour when the team needed him most. New York lost the 1911 World Series to Connie Mack’s Philadelphia Athletics, four games to two.

Although the players, who had come to befriend Faust rather than disparage him, never blamed the affable innocent for the Series defeat, they couldn’t save him, either. McGraw was the king of the castle, and he had no use for his jester once he failed to amuse – and help them win.

So, he turned his back on Faust – refusing correspondence and personal pleas – leaving the simple-minded Kansan to wonder why the greatest pitcher on Earth was no longer welcome on a team he had lifted to such heights.

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

It could be argued that giving a deluded fellow like Charles Faust fuel for his delusion only made things exponentially worse. After all, hope to a man like that necessarily provided his mirage with structure and strength. And, ultimately, it gave his fantasy the hunger it needed to devour what little sense of reality remained around him.

Once professional baseball moved on without him, he went to pieces. He found the idea of being a pitching ace – with Major League experience, no less – without a team to save appalling. A glorious and deserved return to the big leagues became an all-encompassing obsession.

However, financial troubles forced him from the East Coast. back to Kansas, and then out West, where he finally settled in Seattle – near one of his brothers. All the while, he insisted that once his money issues were settled he would make it back to New York in time to help his old team win another pennant. As a final, twisted chapter of his rampaging fixation, he was found wandering the streets insisting that he was walking to New York to resume his baseball career.

On December 1, 1914, Faust was committed to the Western Washington Hospital for the Insane in Steilacoom, just outside of Tacoma. He died there six months later of tuberculosis – no doubt wondering why John McGraw hadn’t invited him back to the Giants to fulfill his inevitable athletic glory.

^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^ ^

Over time, the strange tale of Victory Faust has become more fable than fact – the central character somehow more loveable cartoon than flawed man. Still, if Charles Faust – not Victory – is owed anything by history, it is that he was genuine in his desires and – for a pair of remarkable days – lived every bit of them while people cheered.

And that is the sort of magic trick worthy of the very best of magicians.

Sources:

Schechter, Gabriel, “Victory Faust: The Rube Who Saved McGraw’s Giants.” Charles April Publications, Los Gatos, CA, 2000.

Photos:

http://cdn.bleacherreport.net/images_root/slides/photos/001/238/572/faustcharliethumb_medium_display_image.jpg?1314756038

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/c/c8/Charlie_Faust.jpg/165px-Charlie_Faust.jpg

http://mitchellarchives.com/wp-content/uploads/2008/10/yankees-buy-babe-ruth-article-3.jpg

http://www.insidesocal.com/tomhoffarth/10709_1000101999.jpg

http://images.ha.com/lf?source=url%5Bfile%3Aimages%2Finetpub%2Fnewnames%2F300%2F1%2F4%2F3%2F7%2F1437409.jpg%5D%2Ccontinueonerror%5Btrue%5D&scale=size%5B450x2000%5D%2Coptions%5Blimit%5D&source=url%5Bfile%3Aimages%2Finetpub%2Fwebuse%2Fno_image_available.gif%5D%2Cif%5B(‘global.source.error’)%5D&sink=preservemd%5Btrue%5D

http://www.findagrave.com/cgi-bin/fg.cgi?page=pv&GRid=10709&PIpi=22985112

http://www.baseball-birthdays.com/archives/October/09/images/Charlie%20Faust.png