“Daddy, don’t go!”

Seven year-old Roberto Clemente Jr. knew – absolutely knew – that something was wrong. On that otherwise placid Puerto Rican winter evening, there was a dark and menacing thing waiting outside. Little Roberto could feel it, and his father was on his way to catch a plane that would be flying right into it.

“Daddy, please.”

He was crying now, pleading with his father not to go. Tomorrow might be different, but on that night – December 31, 1972 – there was nothing but sadness and heartbreak in the air. The elder Clemente tried to reassure his young son. He would come back home as soon as he could, but it was important for him to go as quickly as possible.

There was food and medicine loaded onto the DC-7 waiting on the tarmac at San Juan airport, and there were thousands – perhaps, hundreds of thousands – who might benefit from the supplies.

Nicaragua was in pieces. A brutal earthquake days before had left the country in tatters. Though splintered buildings dotted the landscape, it was the human cost that drew the eyes and ears of the world.

However, Nicaragua was a tumultuous place in 1972. Even before the violent shift of tectonic plates brought ruin, there was enough manmade chaos to go around.

The country’s not-so-benevolent leader, Anastasio Somoza, ruled with himself in mind first, his military emissaries – the National Guard – secondarily, and his people lastly – inconvenient dependents with limited importance. The economic and social disarray in which most Nicaraguans lived under Somoza’s selfish rule neither disrupted the dictator’s sleep nor stirred his conscience enough to improve those conditions. So, when the earthquake struck – and the subsequent outpouring of international relief came – Somoza did as he had always done and scooped up as much as he could carry, leaving the Devil to deal with the details.

To make matters worse, the National Guard had followed his lead and looted the neighborhoods they should have been protecting. The asylum was on fire, and the most influential inmates – the ones with guns and money – were too busy playing with their newfound baubles to put it out.

Back in Puerto Rico, the island’s most influential citizen couldn’t stand by idly as nearby Nicaragua continued to disintegrate. He not only felt that it was crucial for him to gather as much as he could to send to those in suffering but that he had to personally escort the goods and use his notoriety to make sure they stayed out of Somoza’s greedy hands. You see, little Roberto’s father was famous – very famous. He was one of the greatest baseball players on the planet and had spent the last 18 seasons proving it to everyone who watched him play.

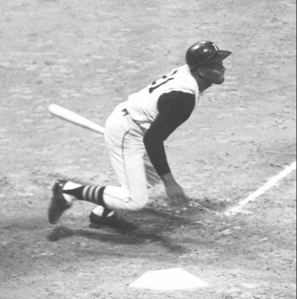

And Roberto Clemente played with a beautiful blend of intensity and grace, an unmistakable fury balanced by remarkable natural choreography. Although his fame in America was dimmed somewhat by not playing in a media hotbed like New York or Boston, he had grabbed his share of the national spotlight in the previous two years with a pair of extraordinary accomplishments.

The first came in 1971 when he led the Pittsburgh Pirates – the only major league ballclub for which he’d ever played – to the World Series title. In the Series, he had hit .414 and was seemingly everywhere on the field, all at once. He’d been involved in nearly every significant play in the seven-game championship set – perhaps, none more impressive than a throw he made from the right field corner in Game 2.

After chasing down a booming fly ball, he planted his foot in the turf and used the natural momentum of his pursuit to turn a perfect pirouette. The ball shot from his hand like a slingshot and carried directly towards third base, narrowly missing an improbable out. He had made the most difficult – and farthest – throw in baseball look more like an artistic expression than athletic exertion, and it became the enduring image of the entire Series.

The following year, he collected the 3,000th hit of his brilliant career on the very last day of the season. It was a mark that only ten other players in the history of the sport had reached. And Clemente had gotten there with his trademark flair.

He hit a line drive into the left center field gap. As he raced into second base with a double – his arms and legs pumping wildly – the number “3,000” flashed across the Pirates’ scoreboard, and it looked as if he was simultaneously running directly into the huge number and his place in history.

In Puerto Rico, he was a national hero. In fact, he was probably more than that, because he was equal parts inspiration, heartthrob, and treasured native son. And he accepted this elevated status with extreme pride and vigilance. He knew how lightly Latin people were regarded outside of their immediate locales and such marginalization never sat well with him.

If his athletic celebrity afforded him anything worthwhile, it was the opportunity to display the pride of his people to the rest of the world. After winning the Most Valuable Player Award for the 1971 World Series, he made his acceptance speech in Spanish, infuriating American broadcasters but delighting his family and adoring country. For years, those same broadcasters tried to address him as “Bob” or “Bobby,” but he politely – and pointedly – insisted on “Roberto.”

When he finally had the opportunity to put his celebrity to true humanitarian use, it was of little surprise that he felt compelled to do whatever was necessary, even if it meant he had to calm down his frightened son before he could even get out the door on New Year’s Eve.

As it turned out, the scary thing Roberto Jr. sensed in the shadows wasn’t lying in wait for his father’s plane it was his father’s plane.

The DC-7 waiting for Roberto Clemente at the San Juan airport was owned by a man named Arthur Rivera, and Rivera only knew a couple of things about flying. One, he wasn’t very good at it. And, two, it didn’t matter because there was money in it. As far as he was concerned, as long as you had a plane, the rest was negotiable.

Among the list of negotiable items was finding a pilot for Clemente’s flight – he enlisted an aviation vagabond named Jerry Hill who had literally been wandering by his hangar the day before. For flight engineer, he asked one of his mechanics to accept the role. And, naturally, he needed to look no further than his own reflection for the plane’s co-pilot.

When Clemente arrived and readied himself to carry out his relief mission, he likely had no idea how hastily and carelessly the plane’s crew had been assembled or that those haphazard selections necessarily affected their ability to make the plane adequately ready for flight. For one thing, they hadn’t bothered to specifically weigh the cargo, only estimating the total.

Officials later determined that the supplies Clemente had thought would bring hope to a broken nation exceeded the capacity of Arthur Rivera’s shoddy aircraft by over 4,000 pounds. The doomed plane was never meant to get fully airborne. The laws of physics guaranteed it.

Still. Rivera needed the money, and Clemente was too focused on getting to Nicaragua to stop the flight.

The first news most Puerto Ricans heard on the first morning of 1973 was devastating. Roberto Clemente’s plane had crashed into the ocean shortly after takeoff. There were no survivors.

The initial sense of disbelief was everywhere. The country’s greatest hero, its embodiment of conscience and soul, couldn’t be gone – turned to vapor as he was rushing to help others. He had to be out there, somewhere, still trying to get to where he was needed – still reaching out to the lost and broken.

One of Clemente’s Pittsburgh teammates, catcher Manny Sanguillen – who Clemente had affectionately called “Sangy” – shared in the dazed sense of loss. In fact, he went directly to Puerto Rico after the news of the crash and dutifully searched the ocean where the plane had gone down, hoping to find a trace of his close friend. Sanguillen dove and dove, for weeks – perhaps, trying to finally convince himself that Roberto was really gone.

Despite Sanguillen’s heartbreaking effort, Clemente’s body was never found. Truly, it was as if he’d been placed on Earth to evoke thrilling memory and profound emotion and then vanished, leaving only his spiritual fingerprints behind to mark a noble and heroic existence.

Daddy, don’t go.

What Roberto Jr. didn’t realize at the time was that his father had no choice. When heroes are called, they cannot turn back, even though their little boys wished they could.

Sources:

Clemente: The Passion and Grace of Baseball’s Last Hero, David Maraniss, Simon & Schuster, New York, NY, 2006

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/c/clemero01.shtml

http://countrystudies.us/nicaragua/11.htm

Photos:

http://media.vcstar.com/media/img/photos/2008/04/20/20080420-194525-pic-254570639_t607.jpg

http://filipspagnoli.files.wordpress.com/2009/03/colonel-anastasio-somoza.jpg

http://i.cdn.turner.com/sivault/multimedia/photo_gallery/0810/history.oct13/images/ROBERTO2(2).jpg

http://www.goldenagebaseballcards.com/showcase/images/59Topps-478Bob%20Clemente.jpg

http://www.baseball-almanac.com/players/pics/roberto_clemente_autograph.jpg

http://www.ct.gov/dcf/lib/dcf/latestnews/images/roberto_clemente_jr_kissing_photo_of_dad.jpg