Sadaharu Oh

Position: First Baseman

Years: 1959 – 1980

Teams: Tokyo Giants, Yomiuri Giants

Bats: L

Throws: L

Why you should care: Oh was unquestionably the greatest player in Japanese Baseball history. His career home run total of 868 still stands as the most ever by a single player, not only in Japan but, in the world. In addition to his remarkable prowess as a power hitter, he was also an exceptional defender, winning nine Gold Glove awards.

Above all else, Oh was a winner.

He led the Tokyo – and later, Yomiuri – Giants to 11 championships in a 13-year stretch, a remarkable run of dominance. Known for his trademark batting stance, Oh was a complete hitter. That stance, which began by standing in one leg, helped to produce a .301 lifetime batting average and 2,786 career hits, in addition to all of those home runs.

After he retired as a player, Oh managed the Giants for five seasons before being hired as the skipper for the Fukuoka Hawks, a post he held for fourteen years. He also won a pair of championships while with the Hawks.

As a final encore, Oh was named manager for Team Japan in the inaugural World Baseball Classic in 2006, and, as befitting his extraordinary legacy, led his team to the title.

The fine print: The laws of physics should have prevented it.

Of course, hitting a baseball while standing on one leg defied any number of conventions. However, Sadaharu Oh did it for 22 seasons. And, more remarkably, did it with such ferocity that he set an international record for home runs that still stands.

For sheer scale, his career total of 868 is astonishing. Consider that such a staggering number is 150 more than Babe Ruth hit, 110 more than Hank Aaron, and over 100 better than Barry Bonds’ Major League record. Not only that, Oh compiled the number playing most of his career within a 130-game schedule, nearly 25% fewer games than the Major League season.

Critics counter with the argument that Japanese Baseball, even today, is a substantially lesser product than the Major Leagues. And the quality was lesser still when Oh played in the 1950’s through the 1970’s. So, some considerable discount inevitably applies when comparing his achievements to those of big league greats like Bonds, Aaron, and Ruth.

However, that argument misses the greater point, namely Oh’s undeniable talent. Trying to translate his Japanese stats into specific Major League equivalents is pointless, if not impossible. It’s not about what he might have done in the U.S. It’s about what he did in Japan. And what he did was extraordinary, no matter the geography.

Still, if an American endorsement is somehow necessary – although it shouldn’t be – to provide Western credibility to his accomplishments, no less an authority than Hall of Fame pitcher Don Drysdale, a ferocious competitor and notoriously unsentimental towards hitters, provided one. “He would have hit for average and power here. In a park tailored to his swing, there’s no telling how many he would have hit.”

Greatness recognizes greatness, no translation required.

Although Oh is remembered almost exclusively as a home run hitter, he was a spectacularly complete player. Perhaps lost in the prodigious gravity of his home run mark are the impressive nuances of his game.

As one of the premier defensive players of his generation, he won nine consecutive Gold Glove awards at first base. In fact, the award itself was not in existence until 1972, thirteen years after Oh’s debut in 1959. So, there’s little question that he would have garnered several more while he was in his prime had they been given out earlier.

At the plate, he was a marvel of discipline, collecting over 100 walks a year for 16 consecutive seasons and amassed 2,390 of them over his brilliant career. That selectivity at the plate narrowed his focus considerably, allowing him to specifically wait for pitches with which he could inflict the most damage. In 1973, he demonstrated the practice with startling efficiency, hitting .355 with 51 homers and drew 124 walks. The performance earned him the MVP award, the sixth of nine he would eventually win.

And when it came to winning, few could match Oh’s resume. He was Japan’s greatest player on the country’s most visible team, the Tokyo Giants. Playing in the epicenter of the nation, he did not disappoint. Teaming with slugging third baseman Shigeo Nagashima, Oh led the Giants to 11 championships in 13 years.

The winning happened so often and with such cool efficiency that the Giants seemed less men and more machine. And Oh’s sleek, flawless game epitomized that precision.

However, lost in the growing expectation of perfection were the struggles of heart and muscle inside the uniforms – none more so than the challenges faced by the seemingly invincible Oh. Despite the fluidity of his play and his placid demeanor on the field, Oh trained relentlessly, constantly seeking improvement. Utilizing martial arts principles from different disciplines like kendo and aikido for balance and leverage, he also incorporated the philosophy of those disciplines into his approach to the game.

Holistically speaking, it could be said that Oh was truly as complete a player as had ever taken the field – body, mind, and spirit in synch with the sport.

Inexplicably, for many, it wasn’t good enough.

Despite three 50-homer seasons and ten more with at least 40 home runs; despite a trophy case bulging with Gold Gloves, MVP awards, and championship rings, he was viewed with tepid interest at home and with skepticism abroad.

In Japan, his teammate Nagashima was always more popular, despite the distance from Oh’s statistical stratosphere. Some claimed Nagashima’s fiery temperament generated more appeal than Oh’s guarded intensity. However, a disquieting cultural undercurrent likely held the greater truth. Oh’s lineage – Chinese on his father’s side – tainted him, socially. Nagashima, a full-blood Japanese, carried no such stigma.

For Oh, the frustration must have been maddening. He simply could not do anything more on the field to win them over. His accomplishments were staggering. Yet, it was Nagashima – albeit a star player in his own right but one from a less prominent constellation – who received national adoration, his adoration.

In the U.S., Oh’s accomplishments, particularly his career home run mark, weren’t regarded with much genuine respect, let alone reverence. Using the Major Leagues as a benchmark, American fans and pundits largely dismissed Oh’s statistical avalanche as an ancillary anomaly performed in a quaint but inferior baseball environment.

It was a strange reaction from two of the world’s most prominent baseball communities to have towards one of the great talents in the game.

However, whether it was a by-product of his martial arts training or the strength of his natural character, Oh handled it all with uncommon grace and honor. And in a society that treasures such traits, its lack of embrace of a heroic figure like Oh is all the more puzzling.

Such is the warrior’s way. Victory in solitude is reward enough.

After his playing days, Oh stayed connected to the Giants, eventually being hired as manager in 1984. However, he could not guide his old team to a title. The championships that were practically a given during his heyday now eluded the Giants, their invincibility a distant memory.

After just over four seasons, the ultimate Giant was forced out – leaving behind the only professional ball club he had ever known.

Fittingly, Oh’s baseball story did not end there. It couldn’t. Being pushed onto the street by the franchise he had lifted to greatness simply would not do as his final image in the game.

In 1995 he was able to take a more appropriate curtain call. He was hired as manager of the Fukuoka Hawks and held the post for fourteen years, where he added two more championships crowns to his winning resume.

And in the course of his tenure with the team, he mentored young players – preaching his philosophy of synergy and effort and molding a perennial also-ran into a consistent winner. One of his protégés, catcher Kenji Johjima, carried his teachings all the way to the Major Leagues – playing four seasons for the Seattle Mariners.

However, two rare blemishes to his otherwise sterling reputation also occurred while he was with the Hawks. On separate occasions, foreign players closed in on Oh’s single-season home run record of 55. And each time, Hawks’ pitchers deliberately pitched around the would-be record breaker late in the season, ensuring Oh’s hold on the mark.

Although Oh denied allegations that he had directly ordered his pitchers to preserve his record at all costs, the damage had been done. Western critics, in particular, were quick to denounce the entire episode and labeled the record as fraudulent. It probably didn’t help that a third similar instance had occurred years earlier when he was managing the Giants. ESPN even smugly ranked the mark among its list of “Phoniest Records in Sports.”

Though, it is curious how the record went from meaning so little in certain circles when Oh set it to sparking insults and indignity when it was prevented from being broken. Perhaps, it is all about who is doing the setting and who is doing the breaking, after all.

Tarnished reputation or not, Oh finally had the opportunity to shine on an international stage when, in 2006, he was named manager of Team Japan for the inaugural World Baseball Classic – a month-long tournament pitting All-star squads from the greatest baseball-playing nations in the world against one another.

The Americans, Dominicans, and Cubans garnered most of the pre-tournament attention. The Japanese were largely an afterthought – skilled but woefully undersized, inescapably vulnerable to the power and strength of the American and Latin players.

Led by Ichiro Suzuki, who had burst onto the Major League scene in the US in 2001 and was widely considered the best Japanese player in decades, Team Japan had two considerable weapons to help neutralize their power deficit – flawless execution of the fundamentals and an overwhelming sense of national duty.

It was up to Oh to harness those elements and channel them into a winning formula in the span of a few short weeks, but he had to convince the players he was up to the challenge first. They were mostly jaded professionals who only knew Oh by his fading celebrity – dusty press clippings from a distant age trying to compete for attention in a high-speed, high-def world. But Oh’s intensity of message won them over.

Perhaps it was because he knew first-hand exactly how difficult earning international respect could be and how rarely the opportunity presented itself. Whatever the genesis, Oh’s directive resonated – honor the game and your country by playing with maximum effort and focus, because the rest of the world will be watching and judging everything you do.

Ultimately, Team Japan outlasted and out willed them all, defeating Cuba in the tournament final to win the title. And in a moment of spontaneous celebration, the players rallied around their manager, abandoning any pretense of professional detachment, and tossed their aging coach in the air with unembarrassed joy.

If he had ever wanted or needed validation on a world stage, that tournament victory provided it.

Back home, Oh received devastating news in 2007. He was diagnosed with stomach cancer. In an agonizing procedure, his stomach had to be removed. However, as a testament to his unfailing determination, he not only survived he was back in the Fukuoka dugout for another two seasons. When he retired after the 2008 season, he left on his own terms – the graceful exit from the game that he deserved.

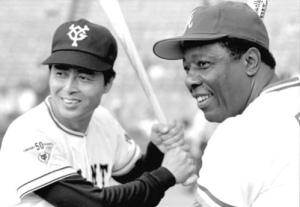

Today, he remains active in the World Children’s Baseball Fair, a charitable organization he co-founded with Hank Aaron to promote the sport to young people around the globe. That the two great sluggers – the men at the center of the decades-old argument about whose career home run mark held more merit – could not only become friends but also joint ambassadors of the game to the next generation of players speaks to the futility of that argument. After all, greatness recognizes greatness, no translation necessary.

Besides, Sadaharu Oh, the hitter who defied physics by balancing on one leg, was more than a stack of numbers to be sifted through to determine some sort of fictitious Major League value. He was a warrior and a champion. He was also a gentleman and a committed student of the game. Mostly, he was a supreme talent who overwhelmed and impressed his competition.

While numbers are certainly part of his story – as they are with any baseball saga – they aren’t the entire one. However, if a number is to be used to reveal something about his remarkable career, 868 isn’t a bad place to start and finish.

Sources:

http://sports.jrank.org/pages/3487/Oh-Sadaharu-Career-Statistics.html

http://www.seattlepi.com/sports/article/Mariners-Notebook-Say-it-ain-t-so-Oh-Johjima-s-1286108.php

http://www.japanesebaseball.com/writers/display.gsp?id=21172

http://www.amiannoying.com/(S(jnptt1zzqixlj155rrnpe155))/collection.aspx?collection=7510

Photos:

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_dfWsvfeutrw/SOVeLlL2y2I/AAAAAAAAAg8/qR2m6Y4GV6c/s320/81+Calbee+Oh.jpg

http://www.japantimes.co.jp/images/photos2008/sb20081029j1a.jpg

http://images.google.com/hosted/life/f?imgurl=0ad1527a60cc7383

http://www.robsjapanesecards.com/20c3.jpg

http://www.aikidojournal.com/blog/media/king0.jpg

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_dfWsvfeutrw/Sc5iSTZ6TYI/AAAAAAAABDY/dDVe2m8DI_Q/s320/09+BBM+Oh+81.jpg

http://4.bp.blogspot.com/_dfWsvfeutrw/Sc5h5KN_xEI/AAAAAAAABDI/OsVwql7_1zM/s320/09+BBM+Oh+back+1.jpg

http://img.snowrecords.com/ep/2/11507.jpg

http://graphics8.nytimes.com/images/2008/05/04/sports/04oh.1.600.jpg

http://seattletimes.nwsource.com/ABPub/2009/10/19/2009674482.jpg

http://i.a.cnn.net/si/2006/writers/jon_weisman/03/09/wbc.format/t1_ichiro.jpg

http://photos.signonsandiego.com/gallery1.5/albums/World-Baseball-Classic/NL_WBC_254262x2245.jpg

http://nbchardballtalk.files.wordpress.com/2011/07/japan.jpg?w=320

http://f00.inventorspot.com/images/156464800_6dbfd9b4d6.img_assist_custom.jpg