Tony Gwynn was good friends with Barry Bonds. Gwynn was also close with Ted Williams.

Perhaps, that tells you all you need to know about Tony Gwynn.

Two of the most combative and complicated personalities in the history of baseball – separated by decades in their playing careers, no less – both found peace and camaraderie with him. That Gwynn smiled as much – or more – than Bonds and Williams snarled (which was plenty), that he was genial and openly joyful while the other two wrestled figurative alligators on and off the field was a testament to the simple unifying power of being a gentleman.

As it turns out, Leo Durocher had it all wrong. The famous curmudgeon posited that nice guys were doomed to finish behind the angry and arrogant. But Tony Gwynn, arguably the nicest guy to ever play Major League Baseball, rarely finished last.

In 20 big league seasons – all with his beloved San Diego Padres, he won eight batting titles, five Gold Gloves, and seven Silver Slugger awards. He was named to 15 All-star teams and finished his brilliant career with a lifetime .338 batting average and 3,141 hits.

In fact, the only time he ever hit below .300 was in 1982, his rookie season, when he hit .289 in 54 games as a 22- year old neophyte. After that, he ran off 19 consecutive years above the .300 line. In his final season, 2001, he battled weight issues and cranky knees but still managed to hit .324 as a 41-year old pinch hitter. It was as if the baseball gods simply wouldn’t let a hitter of his magnitude and remarkable skill fade below the mark that defines hitting excellence, even as his body was failing him.

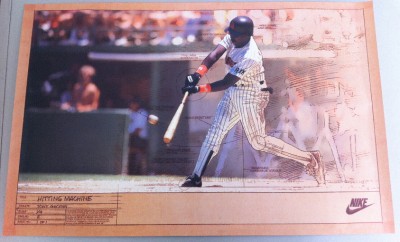

Not that his batting prowess was owed to some sort of cosmic serendipity. Gwynn painstakingly made himself a great hitter, maximizing his athletic potential through patience, study, and physical repetition.

Long before iPads and smart phones brought HD video at our collective beck-and-call, Gywnn immersed himself in the relatively primitive visual technology of the day, lugging a bulky VCR and stacks of video cassettes with him on the road. However, by studying his swing endlessly and dissecting the smallest details, he shaped it and refined it and shaped it some more – like an architect coaxing a sleek structure from a paper sketch.

That meticulous attention to hitting served as the connective source between Gwynn and Williams, because the two seemed to have little in common other than that. After all, Williams made his big league debut 21 years before Gywnn was even born and served in combat duty during two American wars while Gwynn spent nearly the entirety of his baseball life in peace time.

Williams was aggressive and prone to argument and confrontation; Gwynn was calm and gregarious, more likely to shake a hand than slap it away. And they came from different generations in life and different eras of baseball. Yet, the two men knew better than nearly everyone else in the world the how difficult it was to hit a baseball in the big leagues and how few people had ever done it better than they had.

Williams was the last player to hit .400 in a full big league season, reaching the rather impressive figure of .406 in 1941. Gwynn nearly joined him 53 years later, when he hit .394 in the strike-shortened season of 1994. And Williams, who was especially guarded about those he allowed to get close to him, felt a kinship with other great hitters. Considering his resume – 521 career home runs and a lifetime .344 batting average – that distinction was an exclusive one, indeed.

However, Williams developed a special rapport with Gwynn. Whether it was due to the younger player’s excellence at the plate or Gwynn’s endless study of hitting or simply his eternally sunny disposition, Williams gravitated to him like no other player from the current generation. And the same could be said of Gwynn’s affinity for Williams. He revered the legendary slugger and sought his advice on hitting whenever he could.

That mutual respect was never more apparent than during a stretch between the summer of 1999 and winter of 2000. At the 1999 All-star Game at Fenway Park, Williams – whose health was deteriorating quickly – made what turned out to be one of his last big public appearances. As he readied himself to throw out the ceremonial first pitch, Williams had Gwynn steady his shoulder for support while he made the throw.

Given Ted Williams’ enormous pride, allowing such a moment of vulnerability on such a public stage must have been incredibly difficult. That he allowed Tony Gwynn not only to be a part of that moment but to be the one who provided strength and stability was as powerful a statement as he could make about his admiration for Gwynn as a person.

The following year, Gwynn authored a book, “The Art of Hitting”, and had Williams provide the foreword. Gwynn’s book, likely an homage to Williams’ classic manual on batting, “The Science of Hitting”, was the student’s study of the art form. The forward was the teacher’s much coveted endorsement.

The two men also had geography as a common tie. Although Williams was most immediately associated with Boston due to his famed exploits with the Red Sox, he was born in San Diego and got his first professional break there as a member of the city’s Pacific Coast League team in 1936. Gwynn, of course, became such a San Diego icon that he will be forever linked to the place.

Before his Major League glory, Gwynn was a star basketball and baseball player at San Diego State University. In fact, he was so talented on the basketball court that he set the school’s assist record. In retrospect, it was fitting for a man who would become renowned for his generosity to have an official entry in the record books for the number of times he helped others.

As a member of the San Diego Padres, he quickly became the face of the franchise. If there were others made famous by their association with the team, Gwynn’s overwhelming popularity engulfed them. For the twenty seasons he played in the uniform, no one ever thought of anyone else when they thought of the Padres.

Even though he went from a sleek, base stealing speedster – in one four-year stretch, he swiped 159 of them – to rotund veteran playing on wobbly knees, he never lost the two things for which he will always be remembered: that crisp, compact swing and a smile that made an entire city feel good about itself.

The swing, tuned like a Stradivarius over the years, seemed equal parts hard physics, mechanical brilliance, and minor magic. Gwynn was so skilled with the bat that it looked like he actually caught the ball on the surface of the barrel – like a lacrosse player cradling a ball in the pocket of his stick – and then flicked it to an open patch of grass.

As for the smile, it was the signature for one of the game’s most gracious personalities. Reporters marveled at his accessibility and insight, while fans delighted in the homespun delivery. There was never anything pretentious or demeaning about the things he said or the way he said them. He spoke honestly and personably but used humor and wit to make sure the message was available to all – he always made sure to let everyone in on the joke.

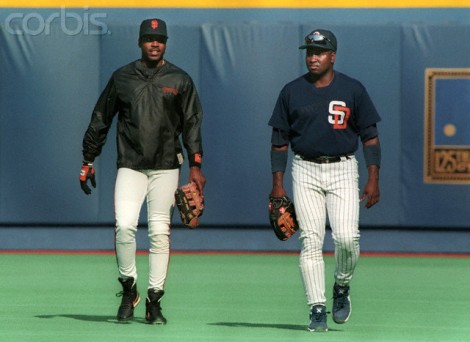

Because of his easy relationship with the media, which bordered on adoration, the press could never quite reconcile his friendship with Bonds – the ultimate villain in the eyes of most reporters. Bonds rarely let anyone in on the joke, because he rarely joked – at least with the media. He was adversarial with the pundits and highly guarded around most everyone else, not unlike Ted Williams.

However, like Williams, Bonds had a special rapport with Gwynn. Perhaps, it was their shared greatness as hitters but also maybe because they shared the same race and the same challenges of contemporary fame. And, maybe, just maybe, Gwynn saw something in Bonds that others had stopped looking for – or more likely – had never bothered to search for at all.

The rest of the world saw Bonds in a black hat, and that was pretty much that.

To his credit, Gwynn recognized that Bonds was a much more complicated person than cartoon bad guy. He once urged Bonds to soften his image a little, to be less abrasive to the media. In other words, Gwynn wanted Bonds to let everyone else see the guy who became one of his best friends in the game. But Bonds couldn’t do it. He needed the edge he got from all of that negative energy.

If Gwynn thrived by charming people and making them laugh, Bonds fed his competitive fire by getting people to root against him. And in the 16 seasons their careers overlapped, they were the best hitters in the game – by a fairly wide margin.

In fact, the year Gwynn rode off into the big league sunset – 2001 – Bonds hit 73 home runs in just 476 at bats (roughly a home run every 6.5 at bats). Three years later, he drew 232 walks, 120 of the intentional variety. Pitchers weren’t just afraid of Bonds, they were scared to even compete against him anymore.

In 2007, Bonds, playing in his final season, passed Hank Aaron as the All-time Major League home run leader. And all hell broke loose.

The whispers of Bonds cheating via PED’s weren’t really whispers anymore. They were loud, angry voices and self-righteous finger points. All of the negative publicity Bonds had accumulated over the years manifested itself into the fervor – perhaps, leaning towards bloodlust – of wanting to see him publicly humiliated as a cheat.

While the baseball world collectively rung its hands every time Bonds reached a home run milestone and argued endlessly over the morality – or lack thereof – of it all, Gwynn, in typical Gwynn fashion, refrained. What he said on more than one occasion with regard to Bonds and his other worldly hitting prowess was that it was the approach that impressed Gwynn the most, not the results. Everyone else obsessed over the muscle; Gwynn marveled at the technique.

As with much else in his life, Gwynn was calm and thoughtful in his professional assessment of Bonds – one of the very few who weighed in on the matter that stayed clear of the chaos and media clutter. As for his friendship with Bonds, it remained intact, because, among his many virtues, Gwynn was incredibly loyal.

That loyal nature, in large part, made Gwynn such a beloved figure in San Diego. Once he set his roots there, he simply refused to leave. Despite the lure of more money and more national fame elsewhere, Gwynn repeatedly signed team-friendly deals with the Padres. In an age of professional sports where players and owners operated – and continue to operate – under a mercenary code, Gwynn chose a place over a paycheck. And the good people of San Diego loved him for it.

Not only was Gwynn an enduring part of the team, he was as big a part of the community. Although he never sought recognition for his public generosity, he earned baseball’s three highest humanitarian accolades – the Branch Rickey Award in 1995, the Lou Gehrig Award in 1998, and the Roberto Clemente Award in 1999. All three awards focused on celebrating the depth and breadth of community giving by a Major League player. Not that the locals needed a trio of awards to know how good Gwynn had been to the area.

As a final ode to his adopted home, Gwynn, who was born in Los Angeles, accepted the head coaching job of the baseball program at his alma mater, San Diego State, less than a year after he retired from the big leagues. It turned out that the old point guard wasn’t quite done dishing out assists.

Even if he couldn’t play in the majors any more, he could help the next wave of aspiring big leaguers get there. Plus, he could still put a uniform on every day and walk out on a baseball diamond and feel the intoxicating energy of the game.

As a mentor, he helped a shy, slightly awkward young pitcher named Stephen Strasburg get prepared for the media blitz that came with being the top pick in the 2009 amateur draft. There was little question that Strasburg had the pitching ability to succeed at the highest level of the game. Some even compared his extraordinary skill on the mound to Tom Seaver. It was the rest of it – the money, media, and ungodly expectations – that Strasburg wasn’t certain about.

So, Gwynn relayed his own pro experience – two decades worth as a Major League superstar – to the young man but fashioned it so that Strasburg could relate to it, could imagine himself in that spot, and how he might best deal with the possibility of big, bright athletic fame.

During the young player’s three seasons at San Diego State, Gwynn also taught Strasburg how to handle the inevitable ups and downs of the game itself. Just as he had done when evaluating Bonds’ swing, Gwynn told Strasberg that it was the approach that mattered more than the results.

Even after Strasburg left the university to pitch in the big leagues, his old college coach never lost touch. There were phone calls and personal visits. And every off season, when Strasburg held his annual 5k charity run in San Diego, Gwynn was there.

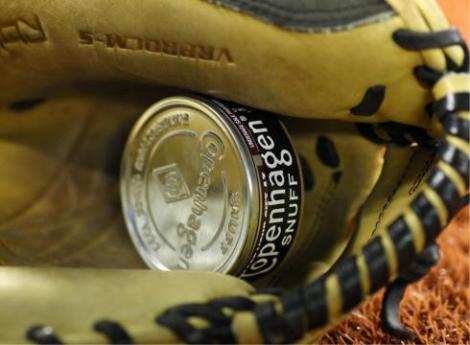

For a man with as few vices as Tony Gwynn, it seemed especially cruel that the one he had the hardest time shaking might have been the one that killed him.

Baseball players chew tobacco. They just do. Perhaps, not all of them but a huge number, nonetheless. The practice has been around the game long enough that many players end up with the habit somewhere along the way. Whether or not the risk is ever fully evaluated – likely, not – the sport’s culture accepts it as part of the landscape. That said, those who chew probably know, somewhere in the back of their consciousness, that it’s a habit that could eventually turn very, very bad.

So, when Gwynn was diagnosed with cancer of the salivary gland in 2010, he was convinced that chewing tobacco had helped to put it there. Some doctors disagreed with the correlation; others wouldn’t pinpoint the origin. Whatever had caused the cancer, the fact remained that he had it, and the prognosis wasn’t good.

Treatment was arduous, relief was sparing, and, ultimately, the relentless cruelty of the disease took what was thought to be untakeable – his trademark smile. Surgery to remove a portion of malignant tumor in his cheek left Gwynn unable to use many of his facial muscles. So, for months, he couldn’t grin – not that there was much to smile about, anyway.

His medical battles forced him to take a leave of absence from San Diego State, and, for the first time in decades, the game wasn’t a part of his life. But he soldiered on, because he had to. If he ever wanted to return to the diamond and his cherished role at his alma mater, he needed to endure the needles and the radiation and the horrible physiological aftermath. Mostly, he needed to beat the disease, because he never backed down from a challenge.

He fought the cancer off two times – stopping the initial spread and beating it again when it returned in 2012. Sadly, when it came around for a third time in 2014, his body had had too much.

On June 16, 2014, Tony Gwynn died. He was 54 years old.

As legacies go, few athletes have ever left a better one than Gwynn. He was a Hall of Fame player in his chosen professional sport and a record-setting amateur in another. His athletic greatness was a fascinating blend of natural gifts, academic grit, and calculated prophecy. He was so charismatic that the press, the public, and the two most difficult figures in the history of American sports all adored him.

He loved the city for which he played for twenty seasons so much that he stayed there after his playing days just so he could teach a new generation of players about baseball and San Diego, all at the same time. And his charity didn’t stop at the gates of the ballpark. He and his wife, Alicia, not only gave money to help the community, they gave their time – hours and hours of it.

At home, his son, Tony Jr., was proud to call his father his best friend and followed his footsteps all the way to the big leagues. Alicia was his high school sweetheart and never left his side – through the glory of his playing days and his utterly bitter fight with cancer.

Perhaps, the most amazing thing about Gwynn’s legacy ,though, is for all of the eye-popping baseball statistics, on-field brilliance, countless friendships, charitable generosity, and personal courage, the one thing that remains in most people’s minds when they think of Gywnn is, maybe, the most simple thing – his smile. His everyday joy was at the core of what he was all about.

So, no, Leo Durocher, nice guys don’t always finish last. Sometimes, they finish way ahead of the rest of us. And we can thank Tony Gwynn and the grand way that he led his life for proving you wrong.

Sources:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/g/gwynnto01.shtml

http://www.encyclopedia.com/topic/Tony_Gwynn.aspx

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/b/bondsba01.shtml

http://static.espn.go.com/mlb/columns/gwynn/1364950.html

http://www.nydailynews.com/sports/baseball/hall-famer-gwynn-dead-54-article-1.1831442

http://drmirkin.com/histories-and-mysteries/tony-gwynn-mr-padre-dead-at-54.html

Images:

http://www.trbimg.com/img-539f78f8/turbine/la-me-tony-gwynn-obit-pictures-012/500/16×9

http://www.gammonsdaily.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Tony-Gwynn.jpg

http://90feetofperfection.files.wordpress.com/2010/09/tonyhrinworldsereis1.jpg

http://img.auctiva.com/imgdata/1/0/1/4/2/4/6/webimg/538052630_tp.jpg

http://www.beabetterhitter.com/text/fundamentals/sweetswing/images/TedWilliams.jpg

http://www.boston.com/sports/baseball/redsox/extras/extra_bases/2014/gwynn_williams.jpg

http://90feetofperfection.files.wordpress.com/2010/09/42-19213500.jpg

http://www.10tv.com/content/graphics/2014/06/16/tony-gwynn-ap-30457689_12279_ver1.0_320_240.jpg

http://media.nbcsandiego.com/images/654*368/Gwynn-Fans-1.jpg

http://www.drugfree.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/Tony-Gwynn-KENT-HORNER_AP.jpg

http://library.sdsu.edu/sites/default/files/imagecache/gallery_full/a-gwynn_tony4-sdsu-052404.jpg

http://natsinsider.files.wordpress.com/2014/06/ap090218045418.jpg?w=320

http://martinisatthebluemax.files.wordpress.com/2013/03/personal-jmf001.jpg?w=620

http://library.sdsu.edu/sites/default/files/imagecache/gallery_full/sp-bkm-61.jpg