He couldn’t hear the roar of the crowd, but he could feel it.

And it was enough. It had to be, because it was all he was ever going to have.

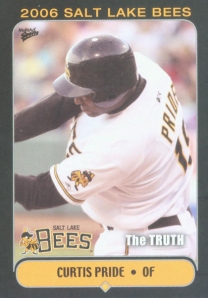

Curtis Pride played baseball with power and speed, crackling with competitive fire. He also played it in utter silence. When Pride made his big league debut in 1993 for the Montreal Expos, he was the first deaf player to reach the majors in nearly fifty years.

A perinatal case of rubella siphoned his hearing. From birth, he never had the rich texture of sound in his life. Instead, he had to rely primarily on sight and touch to replace audio cues.

For an outfielder like Pride, the game was made even more difficult, because he could not rely on calls from teammates to prevent collisions on fly balls. Nor could he pick up fair or foul calls from umpires. He had to see it happening – all at once – perpetually dividing his vision. He needed to visually process so much more than other players it was a wonder that he could keep it all from dooming his play to distraction.

Reaching the major leagues – one of sport’s most exclusive fraternities – is difficult enough using all of one’s senses stretched taut. However, to arrive at such a coveted spot missing one such perceptive instrument is a stunning achievement.

So, when Pride made it to the big leagues in 1993, he had conquered what few others in the history of the sport ever had. And he had done so while squashing his own doubting whispers – the only sound ever available to him.

As a reward for his remarkable journey, he received a standing ovation after his first major league hit, a double lashed all the way to the left center field wall in Montreal. Even though he never heard the cheers, he saw the enthusiastic faces and felt the vibration of the applause. Perhaps, it was an even more profound way to receive such adulation, because he felt it in his bones.

However, the struggle to reach the big leagues is only surpassed by the more daunting task of staying there. Although he had proven himself at each minor league level – at times even performing brilliantly enough to suggest future stardom in the majors – Pride had difficulty with the staying part of the Major League equation.

He wandered through six different big league clubhouses in 11 seasons and played sparingly, only once appearing in more than 90 games in a major league season and often bounced between the minors and majors in the same year. His lone shining moment in the big leagues – aside from that thrilling ovation in Quebec – came in 1996. That season, he achieved career highs in home runs (10), doubles (17), RBI’s (31), and steals (11) with Detroit. He also hit an even .300, the revered hallmark of batting success.

The following year, though, his average plummeted to .210, and the vagabond’s road through the majors beckoned. Although he never hit higher than .252 or played in more than 70 games in a big league season after 1996, he did draw a Major League salary until he was 37 years old.

But he also spent time in Norfolk, Pawtucket, Salt Lake City, and Albuquerque. In all, he played parts of 23 seasons in the minors and independent leagues, a testament to how difficult it is to fully escape the shadows of the lower floors once the penthouse has been reached.

More difficult still, of course, was that Pride had to try to maintain his hold on the big leagues as a deaf player – something that only two others had ever done more successfully.

William Hoy and Luther Taylor claimed that they were never bothered by a common troublesome nickname. The late 1800’s and early 1900’s were not particularly progressive or enlightened times. So, calling a deaf player “Dummy” seemed strangely normal for the age.

However, neither man lacked the smarts, ability, or courage to play the game – and play it well – amidst the myopic thinking of the day.

Hoy made his big league debut in 1888 for the Washington Nationals, who played their home games at the splendidly named Swampoodle Grounds. Although the Nationals finished last, Hoy was one of the team’s few bright spots. He led the league in steals with 82 and finished the year with a team-high .274 batting average.

And he played the outfield with aggressive panache. From center field, he directed his teammates – as a deaf man – on pop ups and fly balls. If the play was his, he would bellow as loudly as he could to signal his bead on the ball. If he couldn’t reach it, he would simply remain silent, tacitly commanding one of his peers to make the play. And he wasn’t timid about his preference for this arrangement.

His teammates respected the dynamic, because Hoy was exceptionally skilled and they all knew it. In 14 Major League seasons, he collected over 2,000 hits, stole 596 bases, and scored nearly 1,500 runs. He was fast and smart and could hit, In fact, he was talented enough to almost make them forget he couldn’t hear.

But there was that nickname.

In time, though, it became a badge of honor, a constant reminder of everything he had to overcome to find success and respect at the game’s highest level.

Just as Hoy was finishing his big league career, a young pitcher in New York was just about to earn a badge of his own.

Luther Taylor played most of his career for the New York Giants and John McGraw, one of the least sentimental managers in the history of the game. So, if Taylor wanted any special dispensation for his deafness, he certainly wasn’t going to get any from McGraw. Not that Taylor ever needed any, though; he was an accomplished amateur boxer in his youth and had an undeniable toughness.

Perhaps, it was that tenacity and his intelligence from the mound that won McGraw over. While the pragmatic skipper lacked pathos, he brimmed with loyalty. Once a player proved his competency and combativeness on the diamond, McGraw willingly became a mentor and protector.

In nine seasons with the Giants, Taylor won 115 games with a 2.77 ERA – including a career high 21 wins in 1904, a pennant–winning year for the New Yorkers.

Although Hoy and Taylor shared scant overlap in their big league tenures, they did have one collective moment of history. In 1902 – Taylor’s rookie year and Hoy’s final season in the majors – the two squared off in game between the Giants and Reds.

In that instant, the two men transcended their insulting nicknames and shattered perceived limitations. If two deaf men could rise to enough athletic fame to meet on a Major League baseball diamond, the alibis of others for lesser dreams and self-limiting expectation seemed all the more hollow.

Thirty-seven years after Taylor threw his last big league pitch in 1908, outfielder Dick Sipek reached the majors with Cincinnati just four years after graduating from the Illinois School for the Deaf. His Illinois coach, Luther Taylor, couldn’t have been prouder.

And no one called Sipek “Dummy” when he stepped on the field.

Although Sipek only played that one season – 1945 – in the majors, he, too, left his mark on the game.

When Curtis Pride made his big league debut forty-eight years later, no one called him “Dummy,” either. By then, perception of a deaf player had progressed to the point where it was merit – and merit alone – that shaped opinions of his play and potential.

Had Taylor and Hoy been alive to witness the thunderous ovation in Montreal a deaf man received for his first big league hit, it would have been that much sweeter to feel the reward for their collective struggle in their bones.

Sources:

http://usatoday30.usatoday.com/sports/college/baseball/2010-04-27-gallaudet-curtis-pride_N.htm

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/p/pridecu01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/minors/player.cgi?id=pride-001cur

http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/14fca2f4

http://sabr.org/bioproj/person/763405ef

Photos:

http://z.lee28.tripod.com//sitebuildercontent/sitebuilderpictures/pride-expos2.jpg

http://blogbeckett.files.wordpress.com/2009/06/heardofme10.jpg

http://cincinnati.com/blogs/tv/files/2012/03/Dummy-Hoy-baseball-card.jpg

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb/4/4b/DummyTaylorLOC.jpg/200px-DummyTaylorLOC.jpg