Apparently, Chief Wahoo was all part of some elaborate homage to Native Americans by professional baseball.

Or maybe not.

As legend has it, the Cleveland Indians’ moniker was intended as a tribute to one of the team’s earliest stars, a fleet footed outfielder named Louis Sockalexis from the Native American Penobscot tribe. If true, it would have marked the first and, perhaps, only time Major League Baseball ever did anything as a legitimate tribute to Native Americans.

The trouble with legend is that it is often difficult, if not impossible, to parse truth from hyperbole – or, in this case, the likely possibility of revisionist history trying to justify an embarrassing past. Besides, taken at face value, the decision to name a team after someone who played exactly 94 games for the franchise over three injury-plagued seasons (1897-1899) seems remote, at best. Add to that the fact the player in question was a person of color, the context of the times didn’t overflow with progressive thinking, and the name change occurred 16 years after his final game with the team, and remote morphs into nearly impossible very quickly. And, if any tribute was, in fact, proffered, the later appearance of Chief Wahoo as the team’s symbol to the rest of the world would have been one of the most curious (and worst) ways to further “honor” Sockalexis.

It’s sad, though, because not only was Louis Sockalexis a remarkable athlete and worthy of our collective remembrance but also because baseball has done appallingly little to discourage our worst stereotypes about Native Americans. In fact, the argument could be made that baseball’s indifference to the ongoing public ridicule of this very distinct group encourages these patronizing generalizations to thrive. It is 2011, and foam tomahawks still wave in Atlanta accompanied by a cartoonish “war chant”, while Chief Wahoo still presides in Cleveland, his outlandish features only slightly softened from earlier incarnations where he appeared little more than a reddish court jester.

However, what the ridiculous chant in Atlanta muffles and Chief Wahoo’s toothy grin obscures are the true voices and images of actual Native American ballplayers and their place in the history of the game.

More than that, they obscure the richness of Native American culture and tradition, as a whole, by reducing it to ridiculous fodder for our general amusement. Certainly, there are those who maintain that such patronizing portraits are harmless and are not intended to offend. However, such a defense conveniently ignores the larger historical context. Native American tribes were driven nearly to extinction through bloody conflict, isolation, cultural ignorance, and callous indifference by the U.S. government. These were not random events with unfortunate results, either. The government had a well-organized plan to rid the country of the “Indian problem.” Intent, in this case, means everything.

So, what, then, does Chief Wahoo have to do with these life-and-death struggles? Of course, on one level, nothing. There are undeniably far greater troubles, past and present, with far more serious consequences to tribes across the country than an insulting mascot for a baseball team. However, lesser problems do not simply vanish, because larger ones exist.

Thus, what may seem like harmless fun at the ballpark should be placed in proper context, namely the long history of forced hardship on Native Americans in this country. However, people will do what they do, and if that means socially indifferent and historically ignorant fans want to swing toy war instruments and bellow a fake war cry thinking it’s cool, so be it. Like wise, Chief Wahoo will still be embraced as though he were just another lovable, harmless cartoon character bearing no likeness to the sacred ancestry of others.

Given the unlikelihood of change on that front, some amount of balance seems in order, which in this case means contrasting simplistic stereotypes with authenticity. And there’s no better way to do this than by telling the actual stories of Native Americans who reached the highest level of the sport. So, going back to the beginning seems the most appropriate place to do that.

Louis Francis Sockalexis was a flash of lightning, literally and figuratively. He had the speed of a track star, the agility and toughness of a record-breaking halfback on the gridiron, and the skill and remarkable hand-eye coordination on the baseball diamond to become a fearsome hitter. He was, indeed, a bolt of lightning on the athletic field – powerful, blindingly fast, and impossible to ignore.

Figuratively, he was also blinding but fleeting in the public consciousness. At every athletic stop, he inspired amazement but lingered just briefly before leaving only vapor and memory. Those who watched him wanted more, but it never came. Through circumstance and mishap, he concurrently inspired delight and evoked regret. In college, at Holy Cross, he hit a blistering .444 in 1895, the last of two seasons he spent on campus. He also starred on the school’s first football squad later that fall, and once, while running track, reportedly won five events in a single meet. But no matter how fast he ran or how skillfully he outmaneuvered opponents on the field he could not elude his personal demons off of it.

A transfer from Holy Cross to Notre Dame in 1896 lasted only weeks before he was expelled for what would be the beginning of a long, regrettable series of alcohol-fueled troubles. Leaving amateur athletics behind for good, Sockalexis signed a professional baseball contract with the Cleveland Spiders in March, 1897. A month later, he was the team’s starting right fielder and displayed the impressive array of skills over which so many had marveled during his collegiate career. After 20 games with the Spiders, he was hitting .377 and became a true drawing card wherever the team went.

However, his demons simply would not let him fulfill his athletic promise. Remember, that Sockalexis became a public figure at a time just a handful of years removed from some of the most violent conflicts between U.S soldiers and tribal warriors and in a place not far from the plains where that fighting occurred. Certainly, a goodly portion of the crowds in front of which he played would have remembered all of that, and many surely would not let the lean, Penobscot right fielder forget it. So, whether he drank because he reveled in the effects of the liquor or because addiction demanded it or because the racial jeers on the field and his social isolation off of it pushed him toward it, his drinking took over everything in his life. Like so many who try to find comfort in alcohol, he crawled into a bottle and never found his way back out.

In July of that season, his promise died.

A serious alcohol-related injury simultaneously sidelined him from the playing field and exposed his excessive drinking to the public. He was never the same player again. He played only sparingly the rest of the year in 1897, finishing the season with a still-robust .338 average and 16 stolen bases in 66 games. Over the next two years, though, he played in only 28 more games before the bottle finally chased him off the field for good. For some, Sockalexis’ fall merely reinforced the image of the drunken Indian unprepared and unwilling to live productively in mainstream American society. (Certainly, Sockalexis was not the first professional athlete whose self-destructive behavior shortened his career, nor would he be the last. So, his ethnicity should hardly be faulted.) Others viewed his early exit from the game as yet another sad chapter in the book of wasted potential.

Given all of that, the glow of his brief career was bright enough to have many openly wonder not whether he would have achieved greatness but to what degree it would have been forged. Among his admirers was Hall of Fame shortstop Hughie Jennings. As Jennings put it, “”Yes, he might have been the greatest player of all time. He had a wonderful instinct and no man seemed to have so many natural gifts as Sockalexis.” And that came from a man who was Ty Cobb’s manager for 14 years. For a player who appeared in fewer than 100 professional games, it’s a rather remarkable legacy. Also, by becoming the first Native American ballplayer to leave his mark on the game, he helped create the foundation for other tribal players who would follow him into the big leagues.

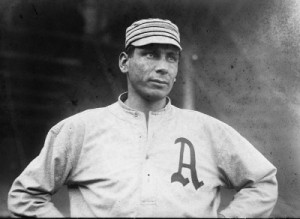

Among those were two of the greatest players of Native American extraction to ever take the field, Charles Bender and John Meyers. Bender, a Chippawa from Minnesota, became one of the more celebrated members of Connie Mack’s string of outstanding Philadelphia A’s teams in the 1900’s and 1910’s. An imposing right-handed pitcher with impeccable control and uncommon savvy on the mound, Bender pitched for 16 seasons, winning nearly two-thirds of his games, and finished his brilliant career with 212 wins and a 2.46 ERA. In his greatest season, 1910, he went 23-5 (an .821 winning clip) with a stingy 1.58 ERA and 155 strikeouts. He capped it off by pitching a three-hitter in the opening game of 1910 World Series, which the Athletics won four games to one. In 1953, he was inducted into the Baseball Hall of Fame.

Meyers, a member of the Cahuilla tribe from California, played nine seasons in the majors and compiled a lifetime .291 average. More than that, he was John McGraw’s primary signal caller on the New York Giants for three straight NL pennant-winning teams from 1911-1913. In particular, 1912 proved to be the pinnacle of his career. Meyers hit .358 with a career-high 6 homers (a respectable total for the “dead ball” era) that season and manned the dish while the great Christy Mathewson and Rube Marquard combined to win 49 games.

Just a year before, he and Charles Bender met up in the World Series, and neither disappointed. The A’s big right-hander won two games with a sparkling 1.04 ERA to lead his team to the championship, while Meyers hit .300 for the Giants with a pair of doubles and a pair of RBI’s.

However, even with their lofty accomplishments, both men were nicknamed “Chief,” a designation less an expression of familiarity and endearment and more a dubious label. In fact, no fewer than 27 players have had the moniker placed on them over time – rather too thick a brush to capture any individual character. Sadly, most were no strangers to generalizations based solely on race, including Bender and Meyers. However, for Meyers, who studied at Dartmouth, and Bender, who studied at Dickinson College, it must have been especially grating to endure the taunts and stereotypes underestimating their intelligence.

Unfortunately, the media of the day not only participated in the name calling it stoked the flames of prejudice with patronizing efficiency. Headlines blared out that teams were “scalped” or did the “scalping” if a Native American player was involved in the action. Such players were also known to be “on the warpath” or casting spells on opponents. Newspaper cartoons distilled the insults even further, combining the disparaging terms with loaded images.

Yet, players like Bender and Meyers persevered. And more would follow.

Though he only pitched two seasons in the big leagues, Moses Yellowhorse gained as much or more notoriety after his playing days as during them. His modest resume includes a 3.93 ERA in 126 innings and a career 8-4 record. As with Louis Sockalexis years before him, Yellowhorse’s legacy rests somewhere between untapped potential and enduring imagery. In 1921, at 23 years old, he used a wicked fastball, estimated to reach the mid-90’s, to craft a 5-3 record with a 2.98 ERA for the Pittsburgh Pirates. Unfortunately, he was limited to just over 48 innings that year before injuring his arm. The following season, he re-injured the arm, and that was pretty much that.

Only it wasn’t.

Yellowhorse was believed to be the first full-blood Native American player in the Major Leagues (his brethren such as Sockalexis, Bender, and Meyers were either known or thought to be of mixed blood). And he was a Pawnee through and through, eventually becoming a respected tribal elder later in life. As such, he came to symbolize so many things to so many people. Moses Yellowhorse, the ballplayer, represented athletic triumph, going from Pawnee, OK all the way to the big stage of Major League baseball. Yellowhorse, the man, whose easy smile and natural charisma gave way to a very dark period after he left the game, represented redemption. Like Sockalexis before him, alcohol took a hold of him and maintained a steady grip for years. Unlike Sockalexis, he simply walked away from his demons one day in order to reach a better life. Finally, Yellowhorse, the elder, represented the wisdom of age and the importance of tradition and cultural pride. Along the way, there were brilliant snippets of a colorful life, including a childhood stint in Pawnee Bill’s Wild West show, beaning the reviled Ty Cobb during an exhibition game in 1922, and having a character in the Dick Tracy comic strip bear a nearly identical name.

Of course, no discussion of Native American athletic accomplishment would be complete without mentioning Jim Thorpe. He was Leonardo in cleats. Decades before Bo knew baseball and football, Jim knew them first. A two-time collegiate All-American and eventual Hall of Famer in football, Thorpe also played Major League baseball for six seasons. Though his baseball career never matched his football greatness, he did finish with a .252 lifetime average. And long before Deion Sanders played in both the World Series and the Super Bowl at different times in his career, Thorpe played in the World Series and won a professional football championship in the same YEAR – 1917. As a curtain call on the diamond, Thorpe saved his best for last, batting .327 in his final season in 1919. His success that year prompted thoughts of what heights he might have reached in the sport had he focused more attention on it and what glory might have awaited if the lively ball period had arrived just a few years sooner.

However, an athlete, even one as phenomenal as Jim Thorpe, only has so much intensity and passion to fuel competitive drive. Asking for equal measures of greatness in both football and baseball at their highest professional levels is an unrealistic expectation. Invariably, there is a lean to one sport over the other. The caveat with Thorpe, though, was an added, extraordinary dimension that Bo Jackson, Deion Sanders, or any other athlete of recent memory cannot touch. In addition to a Hall of Fame football career and a multi-year Major League baseball resume, Jim Thorpe, the proud son of the Sac and Fox nation, was also an Olympic champion. He not only won the Decathlon in 1912 – arguably the most grueling event the Games have to offer – but smashed the world record in the event so thoroughly that his mark would stand for nearly two decades.

The Olympic Decathlon champion has always been commonly referred to as the “World’s Greatest Athlete” and, perhaps, that designation never so appropriately described anyone as it did Jim Thorpe.

In the ensuing decades, a cadre of star players continued the tradition and further enhanced the impact of Native American players in the game. Johnny “Pepper” Martin from the Osage tribe was the fiery third baseman for the great St. Louis Cardinal “Gas House Gang” teams of the late 1920’s and early 1930’s. Martin’s frenetic play resulted in four All-star appearances, a .298 career average, and 146 steals. And he was at his best when the lights were the brightest, compiling a .418 average in World Series play en route to a pair of championships.

Bob Johnson and Rudy York, a pair of Cherokees, were prodigious sluggers in the 1930’s and 1940’s. Both were seven-time All-stars and finished their respective careers with over 500 combined home runs – Johnson hit 288 homers (to go along with a .298 career average) mostly for the Philadelphia A’s, while York hit 277 round-trippers in split time with Detroit and Boston.

The 1940’s and 1950’s saw the rise of a powerful right-hander from the Muscogee tribe named Allie Reynolds. A stalwart on the great New York Yankee teams of the period, Reynolds won 182 games in 13 seasons. He was also named to five All-star teams and went 7-2 with a 2.79 ERA in World Series play. In fact, his championship ring collection could not fit on one hand – he earned a cool half-dozen of them.

In 1966, Jack Aker, a Potowatomie, led the American League in saves with 32 to go along with a stingy 1.99 ERA. In 11 seasons spent mostly with the Kansas City A’s and New York Yankees, Aker saved 123 games with a career 3.27 ERA.

Today, the proud lineage that began with Louis Sockalexis is being carried forward by dynamic young players like Boston’s Jacoby Ellsbury and New York’s Joba Chamberlain. Ellsbury, a Navajo, led the American League in steals in 2008 with 50 and again in 2009 with 70. Chamberlain, a flame throwing right-hander from the Winnebago tribe, finished his first full season with the Yankees in 2007 with a 2.60 ERA and 118 strikeouts in just over 100 innings. In fact, in a moment that undoubtedly would have made Mose Yellowhorse grin, Chamberlain threw a pitch that clocked over 100 miles per hour – the Mach-1 of baseball – in June of that year.

Actually, there’s symmetry in seeing Chamberlain’s searing fastball as a link to the one Moses Yellowhorse threw past hitters ninety years earlier and of Louis Sockalexis flying past second and handing an invisible baton to Jacoby Ellsbury, urging him to sprint home for all of them. Although four very different young men from different places and times and tribes, the common thread of sport and culture weaves them together like the intricate stitches holding a baseball together.

The image of a crimson-tinged player on a green field holding a white baseball under gloriously blue skies is one that has bridged generations. And it should be the image that appears in the mind’s eye when thinking of Native Americans and baseball. More than that, the specific imagery of Charles Bender’s steely–eyed gaze from the mound, Pepper Martin’s ferocity on the basepaths, and John Meyers conferring with Christy Mathewson over the next pitch call should be the focus when tribal spirit infuses a ballpark.

Yet, by and large, what is the Native American experience in baseball still being reduced to? A shallow sing along and a cartoon mascot – 114 years after the Major League debut of Louis Sockalexis. Social evolution in this case hasn’t merely slowed to a crawl, it has stopped entirely.

So, a shift in the way Native Americans are acknowledged by baseball is long overdue. If not for the sake of common courtesy to a long marginalized group, then surely such a change should take place as an acknowledgment of their proud history in the game. Charles Bender – who once outpitched the great Christy Mathewson in the World Series, John Meyers – John McGraw’s sturdy field general, Jim Thorpe – perhaps, the greatest athlete in this country’s impressive sports history, the lost promise of Sockalexis and Yellowhorse, and the latest generation of Native American players like Joba Chamberlain and Jacoby Ellsbury all deserve a symbolic tip of the cap.

From a purely aesthetic standpoint, isn’t that a much more elegant way to view the relationship between Native Americans and baseball? Often, there is beauty in authenticity. The same cannot be said of unwarranted ridicule.

So, if there is still any intent to pay homage to Native Americans by baseball, it’s time to ditch the insulting caricatures and foam war instruments and replace them with the genuinely compelling history of a people and the triumph of their favorite sons in the game, even it comes a hundred years too late.

Sources:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/s/sockach01.shtml

http://www.baseballreliquary.org/story_of_sockalexis.htm

http://bioproj.sabr.org/bioproj.cfm?a=v&v=l&bid=2376&pid=13350

http://research.sabr.org/journals/the-rise-and-fall-of-louis-sockalexis

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/b/bendech01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/postseason/1910_WS.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/m/meyerch01.shtml

http://bioproj.sabr.org/bioproj.cfm?a=v&v=l&bid=991&pid=9594

http://www.baseball-reference.com/pl/player_search.cgi?search=chief

http://www.baseball-reference.com/postseason/1911_WS.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/y/yelloch01.shtml

Fuller, Todd, “60 Feet Six Inches and Other Distances from Home: The (Baseball) Life of Mose YellowHorse,” Duluth, MN, Holy Cow! Press, 2002.

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/t/thorpji01.shtml

http://www.cmgww.com/sports/thorpe/bio/bio.html

http://www.baseball-almanac.com/legendary/american_indian_baseball_players.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/m/martipe01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/j/johnsbo01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/y/yorkru01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/r/reynoal01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/a/akerja01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/e/ellsbja01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/c/chambjo03.shtml

Image Sources:

http://www.examiner.com/images/blog/wysiwyg/image/MLB_CLE_Chief_Wahoo.jpg

http://www.baseballreliquary.org/images/LouisSockalexis.jpg

http://static.howstuffworks.com/gif/chief-bender-hof-1.jpg

http://www.flickr.com/photos/library_of_congress/2163874914/sizes/z/in/photostream/

http://www.baseballlibrary.com/pics/Chief_Meyers_and_Bender.gif

http://www.committee500years.com/images/clip_image004_0000.jpg

http://maggiesfarm.anotherdotcom.com/uploads/JimThorpeBaseball3.jpg

http://castle.eiu.edu/wow/thorOlmp.jpg

http://baseballhistorypodcast.com/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/Bob-Johnson2-150×150.jpg

http://www.sonsofsamhorn.net/wiki/images/c/cc/Rudy-York.jpg

http://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/8/8a/Joba_Chamberlain_pitching_in_May_2008.jpg

![mlb_g_ellsbury3_sq_300[1]](https://rnishi.files.wordpress.com/2011/05/mlb_g_ellsbury3_sq_3001.jpg?w=470)