The first Major League Baseball All-Star Game took place in 1933, which was about 15 years too late.

Granted, that All-Star debut didn’t lack spectacle or star power – seven of the nine starters for the American League were eventual Hall of Famers, while four National League starters later earned Cooperstown entry.

Even the managers carried legend with them. John McGraw and Connie Mack led their respective teams for 86 years between them, collectively winning 19 pennants and 8 World Series titles. Both earned Hall of Fame honors and are still considered two of the greatest managers in the history of the sport.

So, as debuts go, the 1933 All-Star Game was, indeed, gold plated and diamond encrusted.

Still, if the All-Star tradition had started a decade or two earlier, the 1933 edition would have still been played in all of its magnificence, it just would have been the latest in a string of great games leading up to it. Earlier contests would have also allowed a whole slate of star players the chance to shine in such an elite showcase – a chance not afforded in 1933 because they had already left the game.

Consider 1919 – yes, the year of the Black Sox and the eternal tarnishing of baseball’s soul. However, if there was an All-Star game that year, the American League could have matched the 1933 roster with seven Hall of Famers in the starting nine. And that magnificent seven would have included top-tier talents like Ty Cobb, Tris Speaker, George Sisler, and Walter Johnson – all of whom had retired by 1933.

For good measure, the American Leaguers could boast about having Shoeless Joe Jackson, one of the greatest left-handed hitters in baseball history, on the team and having the version of him before he decided to corrupt himself and his sport in the World Series that fall. Harry Heilmann would also be available to them – the only big league player to crest .400, win four batting titles, be selected for the Hall of Fame, and yet remain shamefully invisible in the public’s collective memory.

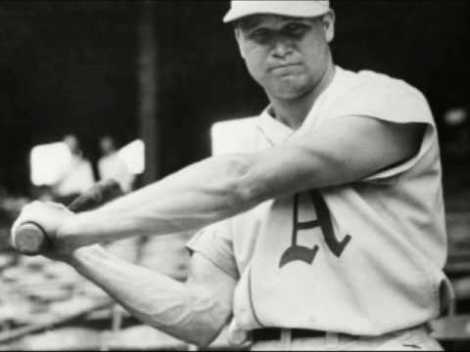

And if the game was close and the team needed an immediate offensive dividend, they could use a 24- year old outfielder from the Boston Red Sox named George Ruth, who was on the cusp of changing the sport forever by tethering the age of power hitting to his booming bat and sling-shotting it forward.

In 1919, Ruth hit 29 home runs, 17 more than anyone else in the majors. He also won nine games on the mound with an ERA under 3.00. So, if the American League needed it, Ruth was capable of launching a homer to grab the lead and then pitching an inning or two to protect it.

As for the National League, they weren’t exactly sacrificial mutton, either. They could roll out five Hall of Fame starters themselves, including second baseman Rogers Hornsby, a two-time Triple Crown winner, and pitcher Grover Alexander, whose 90 career shutouts are still the second most All-time after Walter Johnson.

Coincidentally, the managers for the hypothetical 1919 game likely would have been the same ones who oversaw the actual 1933 contest, John McGraw and Connie Mack – except they would have been 14 years younger and strategically devoted to the more nuanced “dead ball” aspects of play at that time.

Since the “Dead Ball” era (circa, 1900-1920 and so named because of the lack of carry of the ball) emphasized pitching and base running above all else, the 1919 version would have been more stealing than slugging, more spitballs than fastballs, and much more bunting than anyone has ever seen since. That is, such strategy would permeate until Mack decided to play his trump card, Ruth, and then the big fellow would try to put a hole in the outfield grandstands with one swing of the bat.

That mythical 1919 All-Star Game would have been an extraordinary thing to behold, for sure. There would be a few things missing, though – namely, diversity and equality, along with some truly remarkable players.

If the times were more enlightened and the people who ran the majors – as well as the fans who watched – in 1919 had been more accepting and progressive in their thinking, this hypothetical All-Star game would have surpassed the actual 1933 debut in most ways imaginable.

Had star players from the Negro Leagues been allowed to play in the majors in 1919 the infusion of talent and innovation would have been enormous and transformed the sport in ways that might well still be felt today. Such integration would have also allowed two full generations of players to shape big league identities, preserving their baseball legacies in ways only Major League notoriety seems able to do – fair or not – and cast them forward.

But integration didn’t happen in 1919 or 1929 or 1939, it took Major League baseball until 1947 to finally tear down the invisible fence it had built on ignorance and stupidity and fear. And that fence had deprived the big leagues of decades’ worth of historical impact and memorable matchups – not to mention the utterly unnecessary insult and vitriol it directed at hundreds, if not thousands, of faultless players.

The failure to integrate baseball in 1919 is especially galling, because America was only a year removed from its participation in World War I. Among the soldiers sent to fight for flag and country were 40,000 African-American troops. They served honorably, fought with tenacity, and died courageously.

When the fighting stopped and the soldiers returned, African-Americans collectively hoped that the battle sacrifices of black troops abroad merited social progress at home. Sadly, that did not happen. Not much changed – in the factories or political arenas or on baseball fields.

Black men could take a bullet in France fighting a faraway war but could not take the field alongside white players in America.

It was a great shame, not just from a social equality perspective but from a sporting standpoint, too, because many of the best players in the world at that time were black.

To underscore this, if the American League could have fielded seven Hall of Fame players with their best starting lineup in 1919 – a rather impressive number – the African-American community of the time could have done even better. Comprised of black players playing in their own professional leagues that year, an African-American All-Star team would have included eight Hall of Famers.

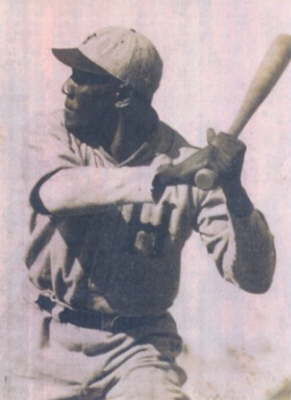

Centerfielder Oscar Charleston could do it all – a power-hitting, defensive wizard with speed. And he did it with the kind of competitive edge that bordered on rage but stayed just controlled enough to be considered productive fury. In 1919, he was 22 and hit a whisper under .400, while belting eight home runs in just under 180 at bats.

Charleston’s outfield mates would have included Pete Hill – a lean base stealer with a slashing, line drive-making swing, and Cristobel Torriente – a stocky Cuban power hitter with surprising stealth. Defensively, the trio’s superb athletic range would have swallowed would-be hits like few others ever could.

Charleston’s outfield mates would have included Pete Hill – a lean base stealer with a slashing, line drive-making swing, and Cristobel Torriente – a stocky Cuban power hitter with surprising stealth. Defensively, the trio’s superb athletic range would have swallowed would-be hits like few others ever could.

As for defense, few players had better reputations for glove work than third baseman William “Judy” Johnson and shortstop John Henry “Pop” Lloyd. Johnson had remarkable defensive reflexes. His ability to charge and field bunts became a trademark of his Hall of Fame skills.

Even though he was 35 years old in 1919, Pop Lloyd could still play. In fact, Lloyd played another 13 seasons after 1919. Like Oscar Charleston, Lloyd had all-around brilliance to his game. On defense, he earned the nickname “El Cuchara” when he played in Cuba for his ability to dig out tough grounders, scooping them to nab base runners as though served up on a tablespoon. At the plate, his tremendous hands allowed him to place the ball all over the diamond and, when needed, he could lengthen the bat and send a booming drive for extra bases.

First baseman Ben Taylor was a gentleman first and ballplayer second. That he had Hall of Fame baseball talent speaks as much or more to his grace and integrity off the field than his magnificent skills on it. As a player, he was a smart hitter with a penchant for getting big hits and a nimble defender recognized for his agility around the bag. As a mentor and teacher, he guided young players for decades after his playing days. His most famous protégé, Hall of Famer Buck Leonard, credited Taylor with not only teaching him how to play first base but also how to be a professional.

Behind the plate, William “Biz” Mackey was everything a great catcher is supposed to be – tough, smart, fearless, and strong armed. When he called a game, pitchers followed him, because he knew the psychology of hitters as well as he knew the physics of pitching. It was a lethal combination. Add to that, a .300 bat and a towering but classy presence, and the result is one of the great catching careers in baseball history.

On the mound, Joe Williams – appropriately nicknamed “Smokey Joe” – had a fastball that rivaled any of the time for sheer speed and intimidation. From Seguin, Texas, Williams had the classic look of a power pitcher – tall, broad shouldered, and deadly serious with a baseball in his hand. Soft spoken off the field, Williams let his searing fastball tell the story. And when it did, that story included a 27-strikeout, 12-inning shutout, a string of 20 straight wins early in Williams’ career, and a poll naming the tall Texan the greatest pitcher in Negro League history.

Like their Major League counterparts, a 1919 Negro League All-Star team could also supply a Hall of Fame manager.

Andrew “Rube” Foster had an aura – an impressive mélange of confidence, defiance, and ambition. As one of baseball’s greatest managers, Foster also had an impressive range of vision. He saw things as they might happen, how they should happen, and how best to narrow the distance between the two.

Above all else, Foster’s vision of the game emphasized speed and precision. The synchronicity of runners flashing from base to base and the hitter putting the ball in play at the just the right moment and location required immense discipline.

Under less demanding leadership, such a bold strategy would have disintegrated into chaos. However, Foster demanded attention and obedience because of his supreme confidence in himself and his players. Subsequently, those players succeeded largely because they simply believed they could not fail.

In 1910, Foster and his players perfected the concept. Compiling an astonishing 123-6 record that season, the Leland Giants may have been one of the greatest teams to ever take the field. Led by Pop Lloyd, the Giants were a blur on offense and seamless on defense, executing Foster’s demanding game plan flawlessly.

During one brilliant stretch, Foster’s teams won 12 championships in 13 seasons (1910-1922). So, in 1919, Foster was still at the apex of his managerial genius.

After he left the dugout, Foster organized the Negro National League and became one of the most visible African-American entrepreneurs in the country. When he was finished, Foster built some of the greatest black baseball teams in history, built the first black baseball league, and, finally, built a legacy which is still regarded as one of the most innovative and successful in the game.

So, if in some parallel universe, the powers that be organized an All-Star game in 1919 and were impartial and decent enough to allow all players of all races to participate, it would have been one hell of a show.

Consider some of the unforgettable showdowns.

Ty Cobb, sharpened spikes and all, racing into second on a steal attempt, in a virtual dead heat with Biz Mackey’s rifle-armed throw to the bag. Walter Johnson trying to sling his legendary fastball past Oscar Charleston, whose lightning fast reflexes rivaled those of any hitter that Johnson had ever seen.

George Sisler belting a ball deep into one of the outfield gaps then waiting to see if Pete Hill could run it down before it hit the turf. And Joe Williams, with his cap pulled down taut, staring down brawny Babe Ruth with the game on the line. All the while, Rube Foster would match strategic wits with John McGraw or Connie Mack – three of the sharpest baseball minds in history.

As icing, all of this could have happened at the rollicking and rowdy Polo Grounds, right on the edge of Harlem in New York City. It was the longtime home of the New York Giants and, with its enigmatic but fascinating oblong dimensions, would have been the perfect cathedral to house this perfect jewel of a game.

The fully integrated 1919 All-Star contest was the greatest game that never happened.

But if it had, it would have had a tremendous ripple effect by the time the American and National Leagues squared off in 1933.

Assuming integration continued – and thrived – the 1933 All-Star Game would not only have included big league greats like Babe Ruth, Lou Gehrig, Jimmie Foxx and Carl Hubbell, no fewer than 16 Negro League stars and eventual Hall of Fame players would have been available as well.

Catcher Josh Gibson, widely considered the greatest power hitter in Negro League history, and outfielder James “Cool Papa” Bell, similarly regarded as the fastest man to play in the league, would have provided remarkably dangerous levels of muscle and quickness to whichever side was fortunate enough to have them.

Gibson hit so many home runs and hit them with such force that the sheer volume – both in number and decibel level – seems overwhelming. Some sources credit him with over 900 homers in his 17-year career, including one launched completely out of Yankee Stadium. While debate may linger on the exact number of home runs he hit, few squabble over the devastating kinetics of his swing.

Bell’s speed could not be reduced solely to the art of the steal – using the number of bases he took over his career as the only metric to evaluate his historic quickness. He learned how to weaponize his speed, turning into as much psychological dagger as strategic windfall. He often beat out routine grounders for hits and would sometimes score from second on a sacrifice fly. And that consistent ability to take an extra 90 feet not available to ordinary players made Bell especially worrisome to opponents, because – as the cliché goes – speed never slumps.

Pitcher Leroy “Satchel” Paige named his pitches, called out hitters, and then backed up all of that bluster the moment the ball left his hand. Paige pitched for 25 seasons, hopping from teams and leagues like a symmetric stone skipping across a lake. Everywhere he went, though, he entertained and impressed. In exhibition games against white Major Leaguers, Paige garnered respect for his considerable abilities from a string of big league stars, including Joe DiMaggio and Babe Herman. They all knew he could play at an elite level; it was only his circumstance that determined where.

To prove the point, when integration finally came, Paige signed with the Cleveland Indians in 1948 and became an important part of the team’s championship season. Even at the age of 42, he still had enough left in his arsenal to go 6-1 with a 2.48 ERA.

In 1933, though, Paige was 27 and still in the prime of his career. Had he played in the All-Star Game that year, he would have undoubtedly pushed Lefty Gomez and Carl Hubbell for the starting pitching nod.

Speaking of Hubbell, his extraordinary run of five consecutive strikeouts against five Hall of Fame hitters (Ruth, Gehrig, Foxx, Al Simmons, and Joe Cronin) in the 1934 All-Star Game remains one of the most impressive moments in baseball history.

It is fascinating to ponder whether or not he would have been able to accomplish the same extraordinary feat if Josh Gibson or Oscar Charleston (even at 37 years old) had been swapped in as part of that fearsome sequence.

It is fascinating to ponder whether or not he would have been able to accomplish the same extraordinary feat if Josh Gibson or Oscar Charleston (even at 37 years old) had been swapped in as part of that fearsome sequence.

As for fearsome clusters of hitters, the Home Run Derby did not become a staple of All-Star festivities until 1985, five decades after the inaugural All-Star contest. However, since hypotheticals are ruling the day (or at least this blog post), imagine an integrated Home Run Derby in 1933.

The American League quartet of Ruth, Gehrig, Foxx, and Al Simmons – Hall of Famers, all – combined to hit over 2,000 career homers in the big leagues. Even today, Ruth, Gehrig, and Foxx remain in the top 30 on the All-time home run list. Foxx, in particular, was so physically intimidating at the plate that pitcher Lefty Gomez once mused, “He wasn’t scouted; he was trapped,” coinciding neatly with his nickname, “The Beast”.

National League representation wouldn’t have quite the same pedigree, but the foursome of Mel Ott, Chuck Klein, Joe Medwick, and Wally Berger includes three Hall of Fame hitters and an aggregate career home run total of more than 1,200. And Ott’s distinctive swing, which featured a prolonged and high-altitude leg kick, would have added a little panache to the proceedings.

Not to be outdone, the African-American contingent would have been comprised entirely of Hall Famers – Gibson, Charleston, Norman “Turkey” Stearnes, and Jud Wilson. Despite a relatively ordinary baseball frame (5-foot-11, 175 pounds), Stearnes won seven home run titles in the Negro Leagues and once led his league in stolen bases, for good measure. Wilson was barrel-chested and massively strong. Despite only being 5-foot-8, many considered him one of the hardest hitters in the history of black baseball. His nickname, Boojum, was derived from the sound his crushing drives made when they struck outfield walls.

The modern day Home Run Derby is – as most modern entertainment pieces are – a glossy, overblown thing designed to fascinate momentarily before being forgotten entirely. It’s laden with product placement and players who bask in the flash and worship of the moment.

Mind you, there’s not wrong with it – as fun, fluffy events go. In fact, most notably, participants are as varied as the international amalgam of the game itself in the 21st century. In that respect, maybe, the derby isn’t all that fluffy and inconsequential, after all.

Still, a home run contest involving the Bambino, the Beast, Boojum, and a power-hitting “Turkey” would have been far more compelling. In it, twelve sluggers – all but one in the Hall of Fame – would unleash their celebrated torque, sending an endless stream of great, big soaring drives out of Comiskey Park in Chicago with the wind howling.

No sips of Gatorade or glitzy scoreboard odometer readings. Just twelve guys in wool uniforms knocking the holy living hell out of baseballs.

And if it came down to Babe Ruth squaring off against Josh Gibson to see who claimed the home run crown, it would have settled an awful lot of arguments that are now forever in dispute.

So, yes, the debut of the All-Star Game came a few years too late, while the integration of baseball came decades too late. And all of the remarkable moments that would have come with better timing of both are left in the regrettable place that all other hypothetical triumph resides.

Sources:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/h/heilmha01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/r/ruthba01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/MLB/1919-batting-leaders.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/h/hornsro01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.cgi?id=charle001osc

http://baseballhall.org/hof/hill-pete

http://baseballhall.org/hof/torriente-cristobal

http://baseballhall.org/hof/johnson-judy

http://baseballhall.org/hof/lloyd-pop

http://www.baseball-reference.com/register/player.cgi?id=lloyd-001pop

http://www.thebaseballpage.com/history/john-henry-lloyd-0

http://baseballhall.org/hof/taylor-ben

http://baseballhall.org/hof/mackey-biz

http://coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/williamsj.html

http://coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/fostera.html

http://exhibitions.nypl.org/africanaage/essay-world-war-i.html

http://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/AL/1933-batting-leaders.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/NL/1933-batting-leaders.shtml

http://coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/gibsonj.html

http://coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/bell.html

http://coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/paige.html

http://www.baseball-reference.com/leaders/HR_career.shtml

http://coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/stearnes.html

http://coe.k-state.edu/annex/nlbemuseum/history/players/wilsonj.html

Photos:

http://jolietlibrary.org/sites/default/files/1930sa/All-Star%205%20-%203.jpg

http://f.tqn.com/y/detroittigers/1/L/K/0/-/-/Harry-Heilmann.jpg

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/d/dc/Ruth1918.jpg

http://sports.mearsonlineauctions.com/ItemImages/000053/53381a_lg.jpeg

https://s-media-cache-ak0.pinimg.com/236x/46/9b/09/469b097580af2e7985f14bf230aefd1a.jpg

http://baseballhall.org/sites/default/files/styles/fullscreen_image_popup/public/externals/cb1e797507872e6cf1c0285af52acaa0.jpeg?itok=xdSXRkZk

http://bloximages.chicago2.vip.townnews.com/pressofatlanticcity.com/content/tncms/assets/v3/editorial/4/6e/46e9288a-982e-5ac6-93c2-55ddc174c077/571407ecd8204.image.jpg?resize=300%2C331

http://s.hswstatic.com/gif/biz-mackey-1.jpg

http://www.blackpast.org/files/blackpast_images/smokey_joe_williams.jpg

http://sports.mearsonlineauctions.com/ItemImages/000017/0280fb46-4019-4e2a-b3e3-191424bea192_lg.jpeg

https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/e/ef/Game1_1912_World_Series_Polo_Grounds.jpg

http://dailydsports.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/08/20150807-2-johnson.jpg

http://baseballguru.com/jholway/image001.jpg

http://sports.mearsonlineauctions.com/ItemImages/000017/3a3faefe-9517-4b59-8aa6-73972eab482e_lg.jpeg

http://dailydsports.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/cool-5.jpg

http://dailydsports.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/20150707-6-satchel.jpg

https://i.ytimg.com/vi/9VxWiHonhkM/hqdefault.jpg

http://stuffnobodycaresabout.com/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Mel-Ott-swing-sequence-1.jpg

https://lh6.googleusercontent.com/-VznPJDAh68g/TWxuim1_4jI/AAAAAAAAAPg/gl1u07TPI0w/s1600/db_Jud_Wilson_20071.jpg

http://mediadownloads.mlb.com/mlbam/2014/07/16/images/mlbf_34578115_th_45.jpg

http://s.hswstatic.com/gif/lou-gehrig-hof.jpg

http://baseballhall.org/sites/default/files/styles/fullscreen_image_popup/public/externals/357864d997ad4349df3881618d01e92b.jpeg?itok=EJ5JhkpR