When the situation called for Superman, he summoned Clark Kent.

As it turned out, the cape was highly overrated.

In 1929, the Philadelphia Athletics were baseball royalty. Their loaded roster included four eventual Hall of Famers – three in the heart of a fearsome batting order; the other, a formidable presence on the mound. From the dugout, the team’s architect, conductor, and patriarch – manager Connie Mack – manipulated his supremely talented chess pieces for maximum effect.

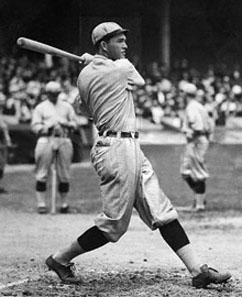

Catcher Mickey Cochrane, outfielder Al Simmons, and first baseman Jimmie Foxx powered an offense with five players who hit .300 or better. And it was Simmons who led them all with the rather impressive combination of a .365 batting average, 34 home runs, and 157 runs batted in.

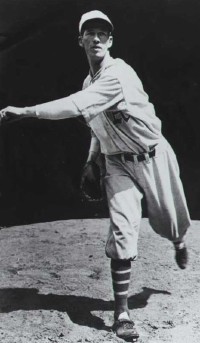

However, it was the pitching staff that truly separated the Athletics from the rest of the American League that season. Southpaw ace Lefty Grove and fellow left-hander George Earnshaw had a combined 44-14 record in 1929, and Philadelphia allowed nearly 100 fewer runs than any other team in the league as well as besting them all in strikeouts.

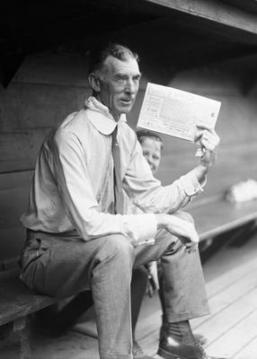

And sitting at the head of the table was Mack, in his 29th season as the team’s manager. He had brought six pennants and three World Series titles home in that span and had established a sterling reputation for leading with a firm but benevolent hand. He also studied the game endlessly earning him the nickname, the Tall Tactician.

So when the brainy, brawny, strong-armed Philadelphians stormed out of the gate to a 39-11 record in 1929, the baseball world took notice. And Connie Mack’s bunch never let up, finishing their trek with a 104-46 record, eighteen full strides ahead of everyone else. Even more impressive, the red-hot Athletics had jostled the legendary New York Yankess of Babe Ruth and Lou Gehrig from the throne – a palace coup of commendable scale.

Advancing to their first World Series in fifteen seasons, Philadelphia was matched up against the National League champion Chicago Cubs.

The Cubs, who were a decade removed from their last championship appearance, had a similarly fearsome cluster of sluggers. Barrel-chested – and barrel shaped – outfielder Hack Wilson hit the ball as hard as he lived. And he lived very, very hard.

In 1929, Wilson fulfilled the baseball part of the equation by hitting 39 home runs with 159 RBI’s. His outfield mates, Kiki Cuyler and Riggs Stephenson, both hit .360 or better and drove in over 100 runs apiece. Cuyler even stole 43 bases to add speed into the mix.

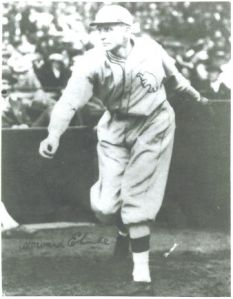

However, the jewel at the center of Chicago’s pennant-winning run was Rogers Hornsby, perhaps the greatest right-handed hitter who ever played the game. And his pedigree was spectacular. A seven-time batting champion, Hornsby hit better than .400 three times and led the league in home runs twice. Although he was 33 years old in 1929 and entering the twilight of his brilliant career, he could still hit and was, therefore, exceptionally dangerous. As proof, Hornsby finished the year with a .380 batting average, 39 home runs, and 149 RBI’s.

The Athletics were going to have their hands full trying to deal with that gaggle of noisy Chicago hitters, and Connie Mack knew it. To further complicate matters, Philadelphia’s two best pitchers, Grove and Earnshaw, were lefties while nearly all of the Cubs’ best hitters were right-handed. And in baseball, the general axiom holds that right-handed hitters see the ball better coming from left-handed pitchers and are more apt to be effective against them because of it.

So, what was Mack to do for Game One of the Series? If he offered up one of his aces into the teeth of Chicago’s greatest strength and that ace got devoured, the tone for the entire championship could irreparably darken. If Mack chose to try to neutralize all of that right-handed thump with a right-handed pitcher, he needed one he trusted enough to accept the challenge.

Enter Clark Kent.

In 14 big league seasons, Howard Ehmke won precisely one more game than he lost. And the rest of his pitching numbers were similarly nondescript. His ERA hovered near the league average as did his strikeout rate, and he allowed roughly one hit per inning. When he threw a pitch, it neither baffled nor intimidated. It mostly got hit.

Still, he was good enough to find gainful employment in the game for over a decade. He just hadn’t been good enough to accumulate any discernible star quality. And on Philadelphia’s star-studded roster, he was the perfect Clark Kent – a neutral face blended almost entirely into the background.

As if to underscore this transparency, he only appeared in 11 games for the Athletics in 1929, pitching a grand total of 54 2/3 innings all season long. Though, when he was used, he did well. Going 7-2 with a 3.29 ERA, it had been one of his better years, brevity or not. And in those sporadic glimpses, Connie Mack must have seen something, because it gave Mack an idea – either utterly brilliant or foolish – addressing the question of Chicago’s heavy right-handed presence.

The answer, he decided, was Howard Ehmke.

Philadelphia’s invisible man took the game’s biggest stage – Game One of the World Series – with the entire sporting public wondering who he was and why one of baseball’s most respected managers selected him over the likes of Lefty Grove and George Earnshaw. However, Mack didn’t have time to worry about such things, if he even cared at all, because the tactician was too busy doing what he did best – outflanking an opponent.

Ehmke, who did not pitch at all over the last two weeks of the season, was certainly well rested. More than that, he was handsomely cloaked in the fog of unfamiliarity. Chicago scouts and hitters had little useful reconnaissance they could use to prepare a game plan, and it showed.

Perhaps, he’d waited his entire life for the opportunity or just sensed the rarity of the moment as it happened. Whatever the motivation, Ehmke’s transformation – when it mattered most – was remarkable. The fact that it happened on the road, no less, in front of a hostile crowd in Chicago made it even more amazing.

His assortment of off-speed pitches, which had been the source of league-wide yawns for such a long time, crackled. Every pitch he threw caused confusion, and the Cubs powerful offense couldn’t touch him. Strike after strike snaked its way from the mound with a relentless drumbeat.

Chicago fans watched in astonishment as Ehmke, the anonymous journeyman, struck out the side in the third – including Hack Wilson and Rogers Hornsby to end the inning.

He did it again in the sixth, fanning Hornsby a second time on his way back to the dugout.

In the seventh, the Cubs put a pair of runners in scoring position – the biggest threat they had mounted all afternoon long – but Ehmke struck out future Hall of Fame catcher Gabby Hartnett to keep Chicago from scoring. The outs and strikeouts just kept coming like a growing stack of split timber in a lumber yard.

In the bottom of the ninth, the Cubs finally scratched across a run, closing the score to 3-1. However, Ehmke fittingly brought the curtain down by throwing one last pitch past a befuddled Chicago player, dispatching pinch-hitter Chick Tolson – his thirteenth strikeout of the game.

Ehmke not only made a devastating and soul-crushing impression on the Cubs and their fans, he made history. His thirteen strikeouts set a World Series record, which stood for another twenty-four years. He also vindicated his manager by pushing every last word of pre-game skepticism back into the mouths of the critics.

Philadelphia went on to take the World Series, four games to one. And one of those games continues to live on in franchise lore, because an unlikely soul took the one chance he had to make a name for himself and wrote it into the record books.

However, Ehmke’s time in the spotlight was brief, as it is for most unexpected heroes. The following season was disastrous for him. He appeared in only three games for Philadelphia in 1930 – the last, a humiliating 10-1 loss to the Yankees, in which he lasted only two innings. In fact, it was his last game in the majors. At 36, he was finished as big league pitcher.

The Athletics defended their championship title in 1930 and had an opportunity to make it three in a row in 1931 but lost the World Series that season to St. Louis in seven games. After that, the franchise chose the bottom line over a winning line and systematically started to pare the roster of its star players and their contracts. Simmons, Foxx, Cochrane, and Grove were eventually scattered to the winds, and the team predictably fell out of contention, becoming a perennial American League doormat.

In 1950, Connie Mack finally stepped down as manager, ending a full half-century residency in the Philadelphia dugout. No manager lived or breathed in the game more deeply than Mack, and none likely ever will. Unfortunately, his final seasons with the Athletics were a cash-strapped misery.

However, his true legacy is firmly secured. He is still regarded as one of the great figures in the game. His unmatched baseball life was filled with too many remarkable moments for it to be otherwise – perhaps, none more so than the day he sent Clark Kent out to do Superman’s work and looked all the more brilliant for doing so.

Sources:

http://www.baseball-reference.com/leagues/AL/1929.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/PHA/1929.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/managers/mackco01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/teams/CHC/1929.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/h/hornsro01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/players/e/ehmkeho01.shtml

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/CHN/CHN192910080.shtml

http://mlb.mlb.com/mlb/history/postseason/mlb_ws_recaps.jsp?feature=1929

http://www.baseball-reference.com/boxes/PHA/PHA193005221.shtml

Photos:

http://www.philadelphiaathletics.org/ppp/images/teams/1929Asteam.jpg

http://static.ddmcdn.com/gif/lefty-grove-hof.jpg

http://www.providentplan.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/06/Babe-Ruth-and-Lou-Gehrig.jpg

http://static.ddmcdn.com/gif/hack-wilson-hof.jpg

http://www.nndb.com/people/046/000085788/rogers-hornsby-1.jpg

http://1.bp.blogspot.com/-gmUSA6vP2p0/TvPEYprVcWI/AAAAAAAARoQ/inyJopXiHA0/s1600/Connie_Mack_2.jpg

http://www.chautauquasportshalloffame.org/images/hehmke4.jpg

http://boston.sportsthenandnow.com/wp/wp-content/uploads/2011/03/FoxxJimmie.jpg